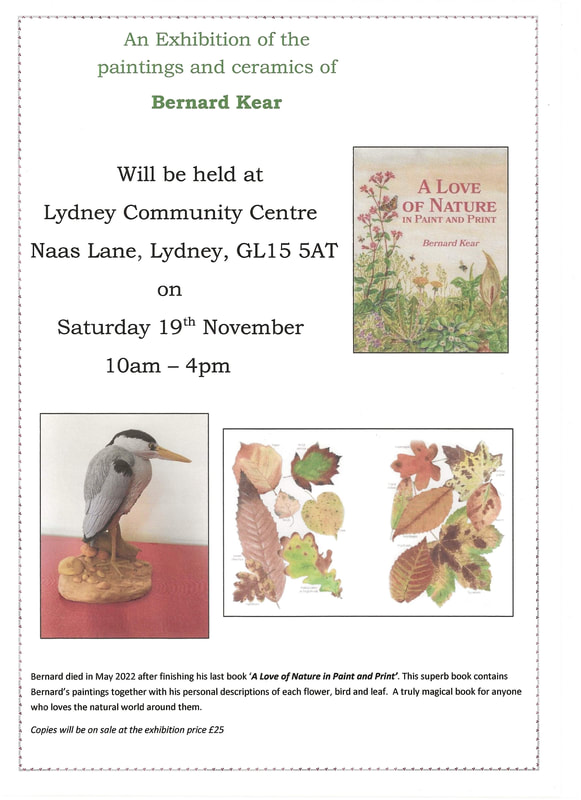

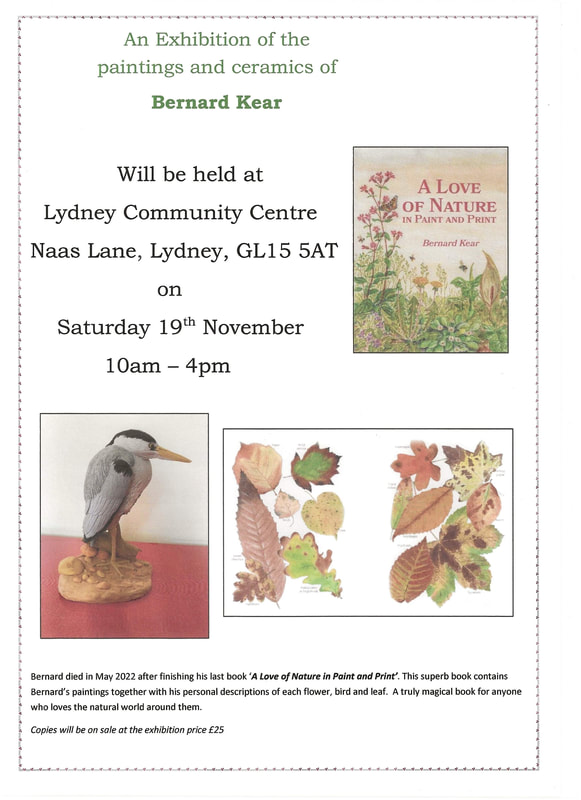

In the early 1990's Bernard Kear produced two wonderfully illustrated books based on his memories of growing up in the Forest of Dean during World War Two. Scenes of Childhood Vol 1 (1992) and Vol 2 (1993) depict and describe a childhood of freedom - camps in the wood, rope swings, fun and games - but also of daily chores to help out - collecting firewood, digging the garden, gathering apples for cider - and the tough realities such as the slaughter of the family pig. All of this is set amongst a backdrop of sharply observed and lovingly rendered depictions of nature and landscape. In addition to the lively and intricate narrative illustrations, there are also stand alone embellishments at the bottom or the corner of pages: a sprinting rabbit here, a stand of toadstools there, woodpeckers, snails, wild primroses, ferns, all beautifully detailed. No surprise then that Bernard's last book was focused solely on this area of interest for him: it was called A Love of Nature in Paint and Print. Along with ceramics made by Bernard, the artwork for the book will be going on show at a special exhibition on the 19th November in Lydney. This will be a great opportunity to see at first hand the work of a talented late Forest artist (and accomplished author), and to get your hands on a copy of his lovely book - on sale at the event.

0 Comments

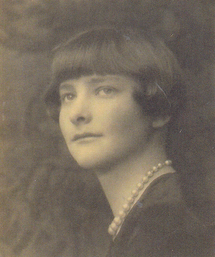

When a teenage boy is found dead in the river Tossy everyone in the tight-knit village of Coedafon assumes that he accidentally drowned trying to retrieve his snagged fishing tackle. When this is quickly confirmed by a hasty Coroner’s enquiry that would seem to be the end of it: the unfortunate death of, it turns out, a disliked and unpopular boy. But…not so for Meg Marsden and her scarred War-veteran husband Andy, recently moved to the village to convalesce and indulge their love of fly fishing. For them, something doesn’t add up. And so begins what becomes a gripping whodunnit. Foul Hooked, written by Islay Manley, is set in a thinly disguised version of Brockweir, the ancient village on the river Wye at the edge of the Forest of Dean. Though not exact in every detail the fictional village where nearly all of the book’s events play out replicates the basic topography and some of the places of the real village and its surroundings. The author and her husband Herbert lived in Brockweir after the War, and like the book’s fictional sleuths they too enjoyed fishing on the Wye. Herbert was employed as a Wye valley river bailiff. After his death sometime in the 1950’s Islay moved away, presumably only then writing this fabulous, and foul, story set there.  Islay, a graduate of St Andrews’ University, was already a published author when she wrote Foul Hooked but her only book to date had been her non-fiction Field and Forest: an introduction to the lives of plants (1955). Complete with her own illustration it was based on her own observations of plants and trees in the Wye valley. It was well-received being “strongly recommended” by the Belfast Telegraph (2nd April 1955, p4b), whilst commended by another reviewer as succeeding in, “showing that plants are as alive and interesting as are animals, birds and fish” (The Fifeshire Advertiser, 19th February 1955, p6d). Whether or not she attempted to also get her whodunnit published during her lifetime is not known, but regardless, her unpublished manuscript remained just that until family of the late author recently decided it was just too good to not make it into print. Foul Hooked really is an incredibly well-written book, engaging the reader from start to finish. Her nephews David and Richard Munro, who both had a hand in bringing the book to print, recall that Islay was an avid reader of Agatha Christie and that comes as no surprise. Islay’s fiction writing is certainly on a par with work from that master of the whodunnit. The pacing of the plot is fantastic, with gripping twists and turns that never feel overwrought or unrealistic in either their timing or what happens. From the start, of course, you will have your theories as to who did what to whom, and which are the ‘good’ and who the ‘bad’ actors in the plot, but like any other really good whodunnit this one will keep you guessing to the end. The action largely plays out within and closely around the village itself. Confined in this way, and with nosey neighbours, village gossip, grudges and suspicions held, the book builds a wonderful sense of claustrophobia felt by reader and protagonists alike. You will have to ask present-day residents of Brockweir if you want to know how much that reflects life in the village today! One thing that local readers may find somewhat discomforting in the book are the disparaging comments made (by the characters) about both rural life and rural people. At one point, hearing the virtuosic piano playing of her friend, Meg reflects that it is “really quite wasted in this country dump”, whilst at another point describing where they live as a, “closed, inbred little community”. These ways of thinking about and describing rural communities were certainly not unusual amongst metropolitan people at the time and they are of course the words of a fictional character. There is nothing to suggest that these reflect the author’s own assessment of country life and communities. Either way, the lead protagonists, Meg and her husband, are so thoroughly likeable and engaging that occasional remarks such as these can, by this reader anyway, be very easily forgiven and in no way impinge on the enjoyment of the book (wherever you live!) There is much to enjoy in this book for the general reader, as well as for any whodunnit aficionados, and if you or anyone in your life is a fly-fishing enthusiast you really must get a copy as there is some lovely descriptive detail in that regard. Thank goodness this fine piece of writing has been brought from obscurity brought into the light of day. Now we know the name of Islay Manley: botanist, illustrator, and writer of a brilliant whodunnit. Foul Hooked (2022) by Islay Manley is published by Brown Dog Books, available online at £8.99 and as e-book at £3.99. Since the start of the Reading the Forest project our team have been rediscovering authors and books with strong connections to the Forest of Dean. Some of these have been known about by local historians and book collectors – though we’ve often been able to dig deeper and discover more about them. But some authors we’ve come across had seemingly been totally lost to the Forest’s collective memory. One of these was Ada M. Trotter, author of Forest of Dean set novels Heaven’s Gate (1886) and Bledisloe (1887). Over the past few years one of our team has become…well, to be honest quite obsessed with finding out all he can about this Aylburton-born writer and journalist. He has been slowly adding his findings to Trotter’s author profile page on the Reading the Forest website, though admits that he’s way behind in sharing all the fascinating info he’s found out. One thing though as eluded him all this time and that is finding a picture of the author. Whilst during the course of his research he’s come across photos of her sister (a prominent US Suffragist), her brother-in-law (Ross-born Geologist, Edward Claypole), and one of her brothers, he’s not found a picture of her anywhere – until now! One of his regular ‘Ada M. Trotter’ searches on e-bay just last week turned up a copy of an 1894-5 annual of the Girls Own Paper – a journal for girls and young women that she regularly contributed to. And amongst the seller’s images of the book was one of the inside covers, and it featured photographic portraits of the contributors. Needless to say, our Trotter enthusiast (obsessive!) successfully bid on the book and recently received delivery. So here, at last, is Ada M(ary) Trotter, author and journalist, born in the Forest of Dean, emigrated to Canada and later lived in the USA. Meanwhile, images (sketches, portraits, photographs) continue to elude us for S.M. Crawley-Boevey, Margaret Mushet, William S. Wickenden, P. J. Ducarel, H. G. Nicholls, Mabel K. Woods, and Catherine Drew. So, if you have or know of a picture of any of these – we would absolutely love to see them!

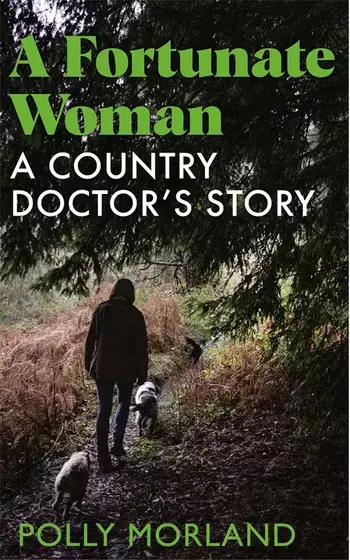

And it too is a remarkable, gripping and inspiring book that itself must surely become recommended reading for today’s trainee GPs.  Poly Morland is an award-winning documentary maker, journalist and author. She came upon Berger’s book by chance whilst clearing out her mother’s house in the summer of 2020. Picking up the dusty paperback copy that had fallen down the back of a cupboard decades ago, she instantly recognised one of the photographs: it showed the very same rural valley where she now lived. ‘Not only was this my home, my valley’ she writes, ‘but I too knew the doctor, his successor, the woman who serves this community today’. Unsurprisingly perhaps, when she contacted her, Morland’s doctor knew of Berger’s book, indeed it was part of the reason she too became a doctor: yes, they should meet. And so began their collaboration on this wonderful new book. A Fortunate Woman owes a great deal to its predecessor in regard to its approach and structure. It’s exact setting is never explicitly named, though of course, as the anonymity in the original was blown by a sensationalist tabloid newspaper piece, today a simple online search will divulge the identity of ‘the valley’ that Eskell and now Morland’s doctor serves. Where Eskell became ‘Sassall’, Morland’s doctor is never named – pseudonymously or otherwise. In both cases this gives their authors licence to exploit techniques more akin to the writing of novel in order to explore the inner lives of their subject. Based on close observation, interview, and in Morland’s case extracts from the personal journal of her doctor, yet not adhering in every detail to exact biography, the authors are free to combine and reconfigure incidents in order to better get at underlying truths. These are of course the stories of individual doctors, replete with biographical detail, yet they are not biographies as such. Rather, the part-anonymity of their protagonists allows these to be stories of doctors more generally; professionals in a role whose motivations and approaches to their work owe as much to more general institutional, social and geographical circumstances, as they do to individual personalities. Both books use anonymised patient consultations and histories as a means to explore the doctor-patient relationship in depth, as well as particular approaches to clinical practice. Alongside the personal histories of the doctors, it is these case histories that provide much of the narrative drive. They also, at points, provide moments of heart-stopping drama. Some of Morland’s descriptions of the GP’s inner thought processes and decision making when faced with rapidly emerging life and death situations are breath-taking. We see a doctor who perceives these situations in all their human dimensions and implications rather than merely as detached professional challenges. Berger and Mohr’s book is now 55 years old, and as GP Doctor Gavin Francis wrote in the introduction to the 2015 reissue of A Fortunate Man, it is now ‘a memorial not just to this exceptional individual but to a way of practising medicine that has almost disappeared.’ It is a book that is to be honest showing its age, not just in terms of the transformation of medical practice, but also in the wider social and literary context of its writing. Berger as author is a commanding presence in the book, untroubled by later academic theories that brought into question the authority of such an unequivocal authorial voice. Its author is almost as much protagonist in the book as ‘Sassall’ is in the life of his rural community. Reading A Fortunate Woman, Morland is also very much precent as author. Whilst her relationship to the doctor, Berger’s book, and the wider issues facing contemporary primary care are clear, they are also far more lightly held by the text, never interfering with the presence and story of the doctor and her patients. Berger’s intense focus on the doctor precluded, as he himself acknowledged, any significant mention of Eskell’s wife Betty who was not only a vital support to Eskell personally (Eskell suffered from depression) but also professionally in helping to run the practice. He was also supported in reality by a cast of pharmacists, district nurses and other professionals – not that you would know it from the book. Reading A Fortunate Man today it is to read a book of its time: the politics, the cultural assumptions, the social concerns expressed through the cases. Without wishing to over emphasise this, it is too, a book written about a male professional, by a male writer. They share a great deal in terms of social circumstances and outlook too, as well as cultural tastes. As Eskell’s late son pointed out, his father relished the many dinner party conversations on art, books and music with the likes of Berger and his friends. This was a period in which both medicine and literature were still dominated by the voices of men. In contrast, the experience of reading Morland’s book today is then one of being blasted by a gust of fresh, clear, contemporary air issuing from its writing and sensibility.

As in Berger’s book the patients are anonymised combinations and reconfigurations of real case histories, but in Morland’s their more familiar contemporary situations, problems and concerns, coupled with her considerable skill as a writer and communicator, make for more fully rounded, more real, more relatable and engaging figures. We read about gender transition, coercive control, Alzheimer's.

There are other changes in the make-up of today’s patients too. Morland’s doctor has far more elderly patients, with their attendant issues of dementia, decisions around care and the wider impact on partners and family, and end of life care too. She has twice as many patients now than Eskell did. Though much of her work is based at the surgery she still makes house calls, the former doctor’s Land Rover replaced now by an e-bike. Morland’s doctor is, all the same, as she describes her a kind of practice ‘grandchild’ to Eskell. Indeed, his former partner was still in place when she started there, and she worked alongside him until he retired. She shares Eskell’s whole-patient approach too, and treasures the unique value of such continuity of care that can only be achieved by a doctor who stays in a practice for years and is deeply embedded in her community. Yet, so much has changed. Morland describes the increasing pressures of a risk management approach to medicine: ‘…standardized guidelines trumps the judgement of individual doctors. Thus by increments the axis has tilted from an emphasis on the patient to an emphasis on disease, from interaction to transaction’. She acknowledges that her doctor’s approach is one that is in its turn at risk of disappearing with mounting pressures on all GPs time and resources. Berger came to know Eskell when he moved to a village near-by to Eskell's soon after marrying his second wife. Remembered by one elderly villager as coming into her parent’s shop to buy cigarettes, he otherwise doesn't seem to be remembered as mixing a great deal outside a small circle. By the time he decided to write about Eskell he’d long moved away, coming to stay for six weeks with the doctor in order to observe him at work. Berger’s descriptions of Eskell’s patient community have drawn much criticism for what some have considered to be glib and dismissive generalisations. To be fair, much of the weight in regard to portraying this community was, by design, intended to be borne by Mohr’s photographs. Even so, there is a sense that Berger just didn’t spend enough time getting to know the character of the people and places in which Eskell worked. In contrast, reading A Fortunate Woman is a far more enlightening experience. Morland, like her doctor protagonist, has an amazing ability to read, understand and describe people. And, like the doctor, living amongst, being embedded in this community, she has a depth and richness of understanding of it gained only through the continuity of living in one place for a length of time. This also enables Morland to describe the valley's landscape over time, and how it changes through the seasons: a practical consideration for a rural GP, but also something to be marvelled at and enjoyed as a salve to the soul on difficult days. In Morland’s hands this is a landscape and natural world that exists on its own terms too, not merely as an anthropocentric backdrop to human drama. Morland clearly has a love of and feel for nature, describing in detail its sights, sounds and smells during the course of the year. This subtlety of observation and description extends to her writing about the doctor too. There are detailed insights into her body language and tone of voice during consultations that seem to place you there in the surgery, witnessing the skill and warmth of this able and empathetic doctor. Reading Morland’s writing we get to know, feel, and appreciate the personality of this place, its people, and most importantly its thoroughly likeable and highly capable doctor. In the latter half of the book COVID arrives, providing a fascinating and gripping GP’s-eye view of the pandemic. Caught up in the practicalities of delivering diagnosis over the phone; deciding who needs admission to hospital with all the risks of infection that entails; and later, arrangements for delivery of vaccines; it is only once the doctor herself is vaccinated that, prompted by the palpable relief of her sons, she acknowledges the risks she has been exposed to during the pandemic. In practical terms, for Morland, the pandemic impacted on another aspect of the book: the photographs. With events and gatherings on hold during the creation of the book due to COVID restrictions, the opportunity to capture the vitality of communal life in the valley was impossible for photographer Richard Baker. What we have instead are images of the doctor decked in PPE, brooding landscape, and patients wearing masks. In this regard we have less to enjoy than in Mohr’s photographs, but Morland’s book is not any lesser for it. A Fortunate Woman is an important book – not least for its description of how we would want our doctors to be, to do their work, to relate to us, to make a meaningful impact on our health and wellness, something that is sadly at risk of disappearing. Whether or not it continues to be a reality, this book provides a valuable blueprint. It is too though a thoroughly enjoyable book to read, a series of fascinating and moving stories; centred upon an engaging and at times quite awe inspiring protagonist - this very particular doctor. A Fortunate Woman: A Country Doctor’s Story by Penny Morland, with photographs by Richard Baker, is published by Picador, price £16.99.

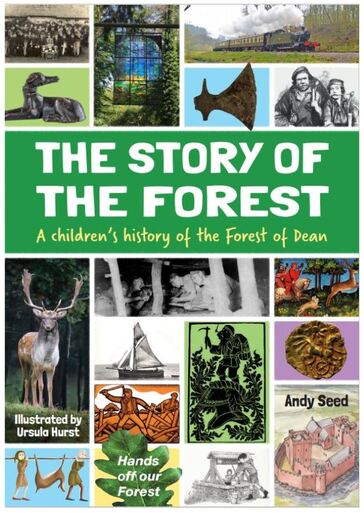

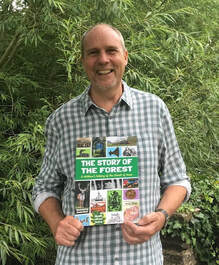

Reading the Forest's Lorna Theophilus has been finding out all about the book, and its hugely successful author, Andy Seed. Award winning Blakeney-based author Andy Seed teamed up with the Forest of Dean Local History Society (FODLHS) and illustrator Ursula Hurst to produce The Story of the Forest: A children’s history of the Forest of Dean. The book - aimed at children, teachers, Foresters, and everyone interested in the history of the Forest - is part of the Foresters’ Forest landscape partnership funded by the National Lottery Heritage Fund. The book took Andy two years to research and write. As well as FODLHS he was also helped by local Freeminers, the Verderers, The Deputy Surveyor and officers of The Forestry Commission, as well as other local people with an interest in the history of the area. Speaking about his approach to the book Andy says that he, “Very much wrote with Forest families in mind and adults who probably know a bit of Forest history, but may not know as much as they’d like to”. Laid out in bite sized chunks the book is packed with facts and questions to get children thinking. Readers can find out about living in the Forest through the ages, starting with the tools left behind by Stone Age ‘Foresters’ in 9000-4000 B.C., through to the establishment of the Forest as a royal hunting ground by the Normans and right up to the modern day. A particular amusing device employed by Andy throughout the timeline in the book is the use of lists of things people didn’t have in particular periods, such as, bricks, cabbages and rabbits in the Bronze Age and aeroplanes, teddy bears and ice cream sellers in the 19th Century. Living in the Forest as it is today it is easy to forget how much has changed over the last few hundred years, for example how industrial it was in the late 18th century and into the 19th century, and how unpopulated it was prior to that. Readers might be surprised to learn for example that Cinderford largely didn’t exist before the ironworks opened there in 1795. Children reading the book can also learn about the Forest when it was home to bears and wolves; compare their school experience with that of Forest children in the Victorian period; and find out about hard lives of hod boys who worked in Forest coal mines. Andy explains that, whilst he wants his book to be enjoyable for all ages, “First and foremost it is a children’s book before it is a history book because if it isn’t right for children it doesn’t work as a book”. However, as a former teacher he also had an eye on its ease of use for education purposes. Copies of the book have been given to local schools as part of the project and the book was launched with the help of pupils from St John’s Church of England Primary School in Coleford. The history of the Forest is approached chronologically in the first chapter before moving into themed chapters; an approach Andy took because he knew would be useful to teachers. The themed chapters cover aspects of Forest history you might expect such as coal, iron and trees and timber, but also a variety of other topics such as crime and punishment, entertainment and community events, and a chapter recommending places to visit. There are photos and illustrations of Forest wildlife both past and present, a wealth of photos of local towns and villages and there is even a chapter to help you brush up on your ‘Vurrest dialect’. Andy was keen to ensure he included things that would draw children in, such as the connection to Harry Potter author JK Rowling, which features prominently in a chapter about notable people. He was, however, careful not to dwell on aspects that might mean less to children, admitting that, “In the end I took quite a few things out because it would have been too long”. Commenting on the brief he was given by the Forest of Dean Local History Society Andy explained that the Society wanted, “A children’s author to get the children’s aspect of it right”. Working with the Society went well, with Andy recounting that, “They were very happy with what I proposed, there was very little argument about changes… and they’re thrilled by the way it’s turned out". It was really important to Andy that the book also looked right, explaining that, “If it looks good then kids will pick it up and then they’ll read it”. The spreads were designed by Sarah Fountain and are beautifully laid out with a river, modelled on the Wye, depicting the timeline which flows through the pages of the first chapter. Helping him achieve the right look was illustrator Ursula Hurst, who Andy says, “Understood exactly what I was after”. The book contains a wealth of photos, and pictures, many provided by local people and groups. There are wonderful original illustrations by Hurst throughout, particularly notable is a Tolkienesque map of the Forest at the beginning. Andy worked collaboratively with Hurst sending her ideas of the type of images he wanted to use and sharing examples of his other books. He is certainly pleased with the results declaring that, “I was able to get [the book] exactly how I wanted it.” Andy Seed is the author of over 30 books including the international bestseller The Clue is in the Poo and The Silly Book series, winner of the Blue Peter Book Award in 2015. His titles for adults include the hugely popular All Teachers Great and Small series. He left teaching to become a writer in 2000, but he hadn’t really thought about writing professionally until after a chance conversation with poet and children’s author Wes Magee. Magee, who was also a teacher turned writer, supplemented his writing with school visits and by happenstance visited the school where Andy worked around the time he (Andy) had started writing some poetry for children. Magee encouraged him, “He said, ‘Send it to an editor, what have you got to lose’”. Andy started his writing career creating content for an educational website and writing educational worksheets to pay the bills, but on his second attempt, his poetry was accepted by a publisher. This was followed in 2003 with his first non-fiction children’s book. Besides his writing, Andy has followed in Magee’s footsteps and he now specialises in school visits promoting reading for pleasure and says his books are the style they are because they’re very good at getting kids reading. Andy is passionate about children’s literacy and says it should be at the heart of education, “It’s a building block, going through the stage of enjoying books, stories, having books read to you, physical books and the great thing about a physical book is you can borrow it, you can lend it, you can share it, you can take it off the shelf, it’s there’. He also argues that reading is an engine of social change and social mobility stating that, “There’s a beautiful correlation between the physical number of books in a house and the educational attainment of a child and that’s regardless of the social group”. For Andy it’s essential that children have reading role models and he is concerned that children are increasingly seeing their parents using screens, whereas in the past they might have been reading newspapers, books or magazines and therefore normalising reading. It was Andy’s family that first introduced him to reading for pleasure. His grandmother bought him his first novel, Stig of the Dump, which he describes as, “one of those books that has a kind of magic in it… you’re transported in the story”, and which he read late into the night under his bedcovers by torchlight. Dr Seuss also strongly influenced him as a child with The Cat in the Hat introducing him to word play; a device he frequently employs in his own writing.  Many of Andy Seed’s books are factual books, which is a genre he was also attracted to as a child stating that, “The book that really I went back to time and time again is The Guinness World Records because I just love facts, stats… that got me into factual books and that’s probably why I write them”. Yet, despite being an enthusiastic reader as a younger child, Andy fell away from reading when he went to secondary school becoming a bit of a tearaway and, according to his website, getting up to lots of naughty pranks. However, a memorable English lesson was to change that and, with it, the direction of his life. He explains, “The usual English teacher was away and we had… the hardest teacher in the school… and he was really cross that he had to cover this other teacher’s lesson”. The substitute teacher told Andy’s class to get on with some work while he marked some books and, finding that he did not have anything to keep himself out of trouble, Andy took a book off the bookcase at the back of the room, “I got this massive thick… book out of the glass cabinet… it was awesome, absolutely awesome… I’d picked up the Iliad… and I was grabbed, absolute grabbed by it… I just got back into reading”. Andy went on to read Homer’s second ancient Greek epic, the Odyssey and he still describes both books as his favourites. His renewed love of reading lead to him experiment with writing, much to his English teacher’s surprise, “I wrote this story… she couldn’t believe I’d written it because up to that point I’d just messed around”. As Andy points out, when it comes to his writing career, “It’s all down to the books really”. The Story of the Forest: A children’s history of the Forest is available from the Forest of Dean Local History society’s website: www.forestofdeanhistory.org.uk/ as well as local outlets including Taurus Crafts and Choice Cards in Lydney and the Dean Heritage Centre in Soudley. You can find out more about Andy Seed on his official website: www.andyseed.com. And...Andy's busy right now completing his latest book all about the fascinating wildlife of the Forest of Dean.

The people, places and landscape of the Forest of Dean continues to inspire writers of fiction, history and poetry. And it is contemporary Forest poetry that's the focus of our new series of the Reading the Forest Podcast as we join in conversation with three Forest poets about their latest work. Hear how and why Maggie Clutterbuck, author of two fine novels, has increasingly turned to writing poetry instead. Discover what brings Stewart Carswell so frequently back from Cambridgeshire to his native Forest both in person and in verse. And listen to Dick Brice as he explains how a decades-long career as a singer-songwriter finally now sees him a published poet. The new series launches on 6th January 2022. To listen all you need do is go over to our Podcast page here, and once loaded just choose an episode and click the play button (we're also on Spotify, Anchor, and Apple Podcasts if you're already signed up to one of those). Whilst you're waiting for the new series you can always listen to Series 1: The Stories Behind the Stories in which we investigate some of the best loved Forest stories.

Trailer for the new series....

Each episode will feature two poems in performance and you'll also be able to watch these readings on YouTube. Here's Dick Brice reading his poem 'A Culture Built on Coal'

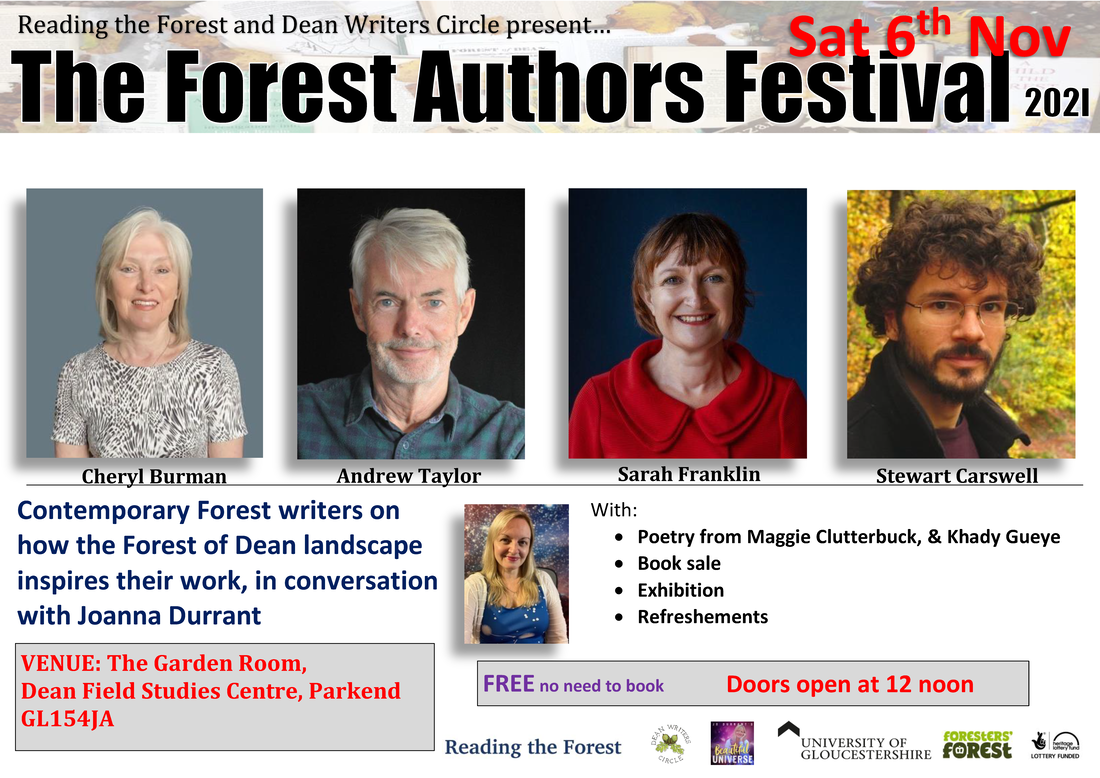

The Forest authors Festival, 2021

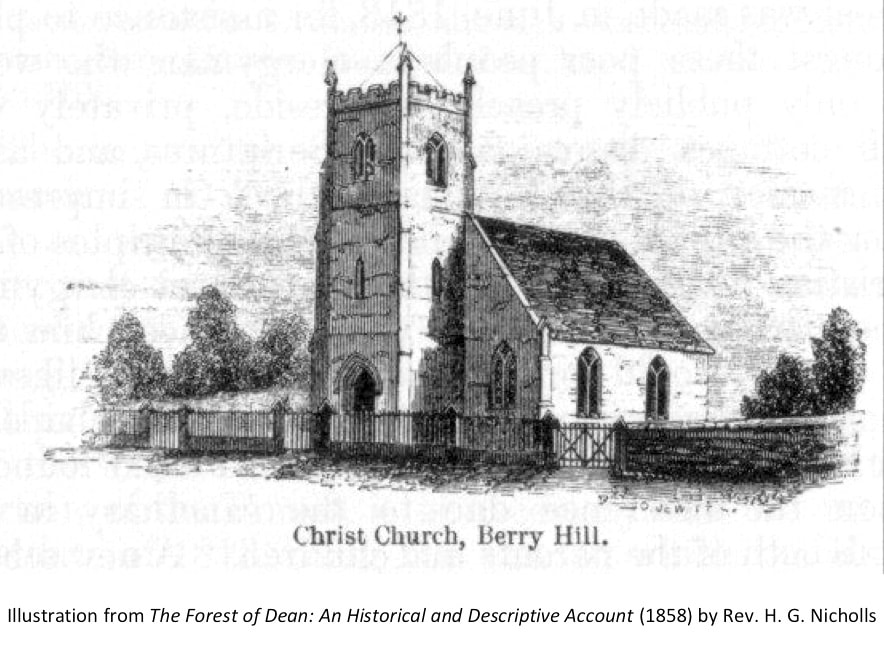

Saturday November 6th Join Reading the Forest, Dean Writers Circle and a host of special guests to explore Forest writers and poets past and present. Head over to our Events page for more details, and to book your free place or just turn up. Please note we've made some changes to this event: doors now open at 12 noon This year marks the 180th anniversary of a remarkable series of poems. It was in 1841 that A Collection of Poems on the Forest of Dean and Its Neighbourhood by Catherine Drew (1784-1867) 'of Littledean Woodside, Gloucestershire' was first published. Now remembered in a memorial plaque at the entrance to Cinderford's St John's Churchyard where she is buried, there was little in Catherine Drew's early life that suggested she would be so remembered two centuries later. From a working-class background, and with only a few days formal education, Catherine seems to have begun writing poetry in later life and was eventually encouraged by her friends to publish them. Printing the book was made possible through money raised from advance subscription. Her slim volume (it contains only eight poems) quickly established Catherine as one of the recognised Forest poets and authors of the first half of the nineteenth century (alongside Richard Morse, P. J. Ducarel, and William Wickenden). At the heart of her 1841 collection is the poem 'The Forest of Dean in Times Past, Contrasted with the Present' - that, according to Forest Historian, and contemporary of Drew, Rev. H. G. Nicholls, was written in 1835. Spanning eleven pages in her published collection, and hundreds of years of Forest history, for us today much of its fascination lies in the insight it gives into some of the social and industrial upheaval Drew witnessed in her lifetime. Recently researcher Steven Carter, deeply interested in the industrial and social history of the Forest, revisited the poem and here he gives us his personal appraisal and appreciation of what he found.  © Courtesy Steven Carter © Courtesy Steven Carter I thought I knew this poem, from the brief extract that appears in The Forest of Dean (1858) by Rev. H. G. Nicholls. That part provides an interesting historical summary of the important half-century prior to the poem’s composition dated by Nicholls as 1835. Since reading the entire poem, however, I realise I had greatly underestimated the work. Catherine Drew’s poem is ‘written in a conversational, plain English’, with simple rhyming couplets (aa, bb, cc, etc.), and is epically long (over 400 lines), without any division into verses. But this great poem is no more ‘simple’ than are the leaves recurring in the Forest; and the many lines are like steps on a long walk, with something to capture our attention at every stride. Like an enjoyable walk, it was never too long and you look forward to retreading the path. The poem’s form or structure resembles a walk: we accompany Catherine on her ramble through the Forest; and our thoughts at times fly down the tramroads, sail along the Severn and spin out to faraway oceans. As someone usually inattentive to poetry, it is hard for me to convey the amazing qualities of Catherine’s brilliant poem. After reading it, I was left with a sense of having truly encountered ‘THE FOREST OF DEAN’ itself. Enthusiastic for local history, I enjoyed every historical reference; whether to the ‘TIMES PAST’ of Catherine’s youth, when lax Forest authority failed to prevent the settlement of squatters and encroachers (such as my own Berry Hill ancestors); or to Catherine’s ‘PRESENT’, where the population had increased and a missionary Church, a reassertive Crown and wealthy Capitalists were transforming life for ordinary Foresters like Catherine herself. The poem captures these big changes and provides insights into my own ancestors’ everyday lives. She asserts her Forest community’s authenticity, integrity, and their useful contribution. She movingly describes their joys and their woes. Her own voice displays their moral character, so unlike many outsiders' demonising caricatures of Foresters as uncivilised, wild and lawless folk. But neither history nor Foresters are the main subject of this poem. Catherine offers more than mere historical utility, more than a mine to dig out golden nuggets of history. Beyond this, we encounter directly and cumulatively the Forest itself. Catherine declares her theme to be ‘Dean’s ancient forest’, where she ‘was born and bred’, ‘The sweet asylum of my youthful days’, where ‘I dearly loved to tread’. But now ‘I’m growing old’, entering her fifties, she looks back ‘and pleased survey, Those scenes that did my youthful thoughts employ’. She is happily content the Forest has formed the stage and fabric of her life: Nor would I change thee, wild romantic wood, Though she lived to be 82, this great work now serves as her ‘Farewell, old Forest dear, farewell to thee’; her tribute and celebration, in which she depicts the changing Forest during changing times. Catherine’s remarkable achievement, for me, is that she succeeds in her theme and portrays so well the ‘Dean’s ancient forest’. 'This is a poem that is utterly and inescapably rooted in the Forest [...] Hers is poetry that is tied irrevocably to the Forest of Dean: it could not be transplanted to another place'. (Reading the Forest: A History and Analysis of Forest of Dean Literature, 2019) She provides a giddying journey through the Forest in dramatic, fast-moving scenes, depicting tiny details, wildlife and beautiful nature; human inhabitants, with their joys and sorrows; tramroad routes to Bullo Pill and vessels that ride the Severn; and she even envisages the timber of the Forest becoming ships riding the oceans and defending the Empire’s furthest reach. Her panoramic view to me reflects how Foresters might 'take in' the Forest. Not seeing just one single point of focus, but rather the eye flowing near and far, with senses overwhelmed by the ‘everywhere-ness’ around you. She sees a tree or a sheep, which grows and branches out into many thoughts. She emerges as someone rooted, knowing the Forest thoroughly, describing not just what is immediately visible, but an underlying depth. 'Hers is a poetry that talks of the Forest of Dean simply rooted in her own experience and knowledge of it, and expressed through a deep love of and loyalty to it as a place [...] Hers was a poetry then that[…] seems to have been primarily enjoyed by readers in the Forest of Dean, a readership whose pleasure was derived from a recognition of the history, places and people of the Forest of Dean in which they lived.' (Reading the Forest: A History and Analysis of Forest of Dean Literature, 2019) Catherine does something else, as Jason Griffiths (above) explains, that can be seen in other Forest literature. She conveys the relevance and presence of the past alongside the present – the past never feels left in the past as so much of it is evident in the landscape. As Dennis Potter put it, the past is always running alongside us and can at any point grab us! Thus, this distinctive place is ‘space infused with meaning’, with its own ‘unique history and character’. 'The specificity of her work to the Forest, her admiration for working people like herself, and her plain direct style, did much to endear her to these local readers'. (Reading the Forest: A History and Analysis of Forest of Dean Literature, 2019) After following her wanderings, it is like your mind has been spun through and around the Forest; and at the end the jigsaw pieces fall together into something resembling completeness. Catherine’s Forest is both up close, there for you to touch, feel and breathe; and yet vast, magnificent, and transcendent; the pulsating heart that gives life for all else. This Forest feels like the centre of the world and, like tree roots spread invisibly below, so the Forest reaches invisibly to the world’s end. In reading and enjoying this marvellous poem I identified ten merging scenes: 1. Freeminers Catherine’s poem opens with her remembering her youth, enjoying the natural wealth of the Forest, its birds, flowers and groves. Soon though she turns to the Forest as a lived and worked environment, both past and present, a lived place rather than an individual experience of nature. She is prompted by the landscape to contemplate a time when the Forest was sparsely populated by only ‘a few free miners’. Catherine narrates the early origins of freeminers’ rights and moves up to more recent times. None but a few free miners then lived here… But noble miners, there have been, I ken, By their old works, stout able-bodied men… She laments the incursion of the ‘foreigners’, i.e. those wealthy capitalists, born outside the Forest. In times past, ….firm and sure were made the Forest laws… But now the foreigners have got the game. Catherine presents not some mythic past Golden Age, but an actual time and place she knew. Her poem is no generalised, idealised forest. Instead, she is rooted in this particular Forest and actual historical times. Her descriptions are not romanticised nor sentimental, but real, matter-of-fact and from her own experience, brief yet powerfully vivid. For example, on free miners’ daily risks, Sometimes I’ve known a faulty rope give way, And plunge them headlong from the light of day. She also challenges the traditional denigration of her Foresters: … don’t colliers despise, Who underground their useful lives destroy, While you enjoy the air, and light of day. 2. Deer Hunt Her ramble comes next upon a deer hunt. The deer ‘shifts and winds in hope thus to evade,’ Until at last, spent out, he slacks his speed, Then Ranter foremost, quickly makes him bleed. The scene is vivid, yet economically told, and without sentiment. After their sport, the huntsmen move away, Unto some neighbouring tavern, and enjoy The good sirloin… The hall resounds, With noisy mirth till wine their senses drown. 3. Tyranny of the Foreigners Catherine contrasts her present, marked by ‘tyranny’, with the distant ‘old times’ of Berkeley, who was ‘good as well as great’, when free miners proved their character in a clear demonstration of loyalty. A Great Rebellion broke out in Scotland, probably the last Jacobite uprising for the Stuart cause in 1745, whose invasion of England reached as far south as Derby. ‘The Foresters crossed the Severn, to join Earl Berkeley’s volunteers, in such numbers as to acquire the appellation of “Berkeley’s ducks”’. Forest of Dean poet Richard Morse also celebrated their bravery: When the throne was endanger’d by traitors,… To oppose them the Foresters sent a brave band, Determined the rebels’ approach to withstand. (From 'The Foresters' Song', Lays of the Forest and Other Poems, 1840. In: A Native Forester, 2012, by David Adams & Chris Nancollas.) Catherine characterises Berkeley’s days as a time of freedom, when, …no tyrant did oppress, And although poor we did not know distress; For all industrious, till’d his little land, And built his cottage… Such freedoms and traditional social bonds ‘are done away’, swept aside by the eruption of the early industrial revolution into the Dean. Now, in Catherine’s present, ‘foreigners over we free miners crow’ and ‘now there’s tyranny enough I know’. The old moral code has broken down, so ‘the honest labouring poor’ are despised and face abuse, even ‘when we do not offend’. Catherine reasserts morality’s demands: Let us by labour earn our daily food, We wish no more, and range our native wood… Give us but labour, and its due reward. Any power from unions was still decades away. Catherine’s only answer to ‘distress’ is to reaffirm the traditional, two-way loyalty; and to insist that those with power must recognise that the country’s good includes taking responsibility for the poor: [You] must know the peasantry do bear a part. Their useful lives and liberties defend. 4. Oak Tree Catherine next remembers resting her ‘weary limbs at noon’ under the ‘friendly shade’ of ‘the brave oak’, ‘a real majestic tree’. But now it is marked ‘to be cut down’. The woodman levelled this ‘monarch’ and immediately men and boys with ‘jovial jests’ and a rosy maid singing cheerfully, all labour upon ‘his limbs’ until sunset. A century back ‘thee’st been a noble shade, to cattle’, but now destined for the Navy, thou’lt plough the deep, … Triumphant o’er the ocean may’st thou ride. Even the ‘sweet peace’ enjoyed by ‘free-born Britons’ is thanks to Forest Oak, ‘A surer bulwark than the China wall.’ 5. Lightening Strikes At first tinge of light, ‘The labouring man does to his labour rise, …Then calls his boys’. Walking to work, they shelter from a storm, but a lightening shaft strikes dead his son John. Catherine captures the family’s grief, simply but effectively; “What will poor mother say, how can we go, Back to our cottage to let mother know?”… The storm is spent, and nature seems at rest, But still, the tempest rages in the breast. 6. Sheep A young shepherd goes ‘with aching heart’ to tell his employer that one sheep has been stolen. This ‘good old man’ is philosophical: Cheer up my man, ‘tis folly thus to grieve, For all thy tears, will never catch the thieves; Come, fetch a mug of my best ale, and drink Success to honest men… 7. Pretty Milkmaid Sally Next, we are with ‘pretty Sally’, ‘The pretty milk-maid’ as ‘she hails the early dawn’. She is the one 'For whom young Collin sigh’d, but sigh’d in vain'. Catherine here communicating the story in a single line. 8. Holy Trinity Church The Church had once been distant. Then at Berry Hill it first divided and then transformed the Forest community. It has now become a ‘blessing’ for Catherine’s community. At Holy Trinity, Rev Berkins, ‘our much esteemed friend’, is a ‘grand pillar of our forest weal’. And more than all – thee faithfully dost preach, The very doctrine that our Lord did teach. Reflecting on that churchyard, ‘Beneath these sods’ all will lie, men and masters: No envy here – nor there no tyranny; The conqueror death has ended all dispute. 9. Tramroad Journey Catherine reflects on the ‘monied men’ who ‘come here to speculate’ and who had, during her lifetime, so transformed the Forest with noble houses, tramroads and deeper pits. Protheroe! Thy name is to the Forest dear, For many thousands thee has ventured here; Deeper thy pits than any here before, The lowest vein of coal for to explore. Catherine might not have so praised Protheroe, the largest by far of the new entrepreneurs, had she known that his ‘many thousands’ had ultimately derived from the Transatlantic Slave Trade and enforced labour on West Indies sugar plantations, the suffering of thousands of enslaved Africans. She does lament, however, that before such ‘monied men’, It was much better for the labouring poor; Men loved their masters – masters loved their men, But those good times we n’er shall see again. Catherine regrets the loss of the closer bond that existed when local Foresters were in charge. Under those masters honest men did thrive, But thanks to God there’s Bennetts still alive. Catherine refers here to James (1783-1841) and Thomas (1781-1861), two brothers prominent in the 1841 Coal Awards. In 1841 over 400 colliers accompanied James Bennett’s coffin from Drybrook to Mitcheldean. His son, Forest industrialist Timothy Bennett (1804-1861), was Mitcheldean’s greatest philanthropist. Here, Catherine’s appreciation was not misplaced. Catherine also remembers when Cinderford was ‘a wild unpeopled spot’. But now there’s houses where the brambles grew. She next traces the tramroad route, ‘down through Soudley Green’, into the tunnel, passing the Hay Hill estate of ‘The good old Squire’ Jones, ‘the Foresters’ best friend’, and on to Bullo Pill wharf. There, forest coal is loaded onto vessels that will ride the Severn tide ‘for Gloucester, Worcester, and elsewhere’. 10. The Foresters’ 'Manifesto' Adoring and proud of her Forest, Catherine also defends the people that Forest gives birth to. She claims an honest dignity for her Foresters. '[She] is no radical; rather she is a poet who reflects her own perception of the times and her own moral position in respect to her own economic and social situation and those of her fellow Foresters. She is at pains to point out that money in itself is no indicator of moral superiority. Drew’s view is that the working men and women, the labouring poor, should value what they do have and endure, and in some respects this alone makes them better people than the shallow and sometimes morally questionable rich.' (Reading the Forest: A History and Analysis of Forest of Dean Literature, 2019, p78) In her ‘A Word to the Chartists’, Catherine castigates the Chartists and advocates instead individual moral reform. 'Drew in this respect tends towards the socially conservative and throughout her published work is an advocate of the dutiful, stolid working life as a route to a morally rewarding existence. Drew advocates, for women in particular, a safe and conservative life.' (Reading the Forest: A History and Analysis of Forest of Dean Literature, 2019, p77) She frequently demonstrates an acceptance of the prevailing social order. Such acceptance, however, is far from uncritical and is perhaps born of necessity. She regrets the loss of the traditional social bonds, ‘those good times’ when 'Men loved their masters – masters loved their men', and contrasts the harmonious ‘old times’ of Berkeley, who was ‘good as well as great’, with the ‘tyranny’ of the ‘foreigners’, who ‘over we free miners crow’. The 1831 riots demonstrated her community’s relative powerlessness and their lack of options in the face of these new ‘moneyed men’ like Protheroe, who so easily associated with the Crown and the Dean Forest Commissioners in imposing a new settlement on Catherine’s world. She is critical of all undeserved disapproval of her Foresters. She denounces social hierarchies that lack genuine moral foundations. Failure to consider the common good, pay a proper wage or even failure to provide work, she condemns as ‘tyranny’. She is as assertive as the times allow, judges people’s true worth and roots her claims in the God-watched natural moral order. Her concluding manifesto seeks adjustments that better consider the Foresters’ needs. She calls on the new elites to care for the poor; and calls Foresters to respect themselves, regardless of how others decry them. Her own evident honesty and integrity requires us to question the then prevailing criticisms and stereotypes that outsiders imposed on those Foresters. In her poem we can respect these earlier people with their straight-forward moral code, their struggles and their cares. Then think my friends upon the labouring poor, Even today Catherine’s Manifesto sounds powerful. Writing in the pandemic, I am reminded of the impressive courage, calm and kindness many ordinary workers display, like, for example, those in supermarkets, amidst the panic buying and sometimes even customer rudeness and abuse. In Conclusion...  © Courtesy of Liza Gouge Daniels © Courtesy of Liza Gouge Daniels Catherine Drew’s spectacular achievement and enduring legacy is to reflect the ‘Dean’s ancient forest’ in her words. She provides the nearest we might approach to walking the woods both in her TIMES PAST, the late-eighteenth century Forester’s world; and in Catherine’s PRESENT, the aftermath of the invasion and partial dispossession by the ‘monied men’, the world of the new settlement being established from the Dean Forest Commission and legislation of the 1830s. What might have been lost, Catherine’s precious poem has preserved and made accessible for later generations. Even more, we grasp the ungraspable, a sensing of the Forest as a whole, transcending its boundaries, transcending time, a living entity, an overwhelming mystery encountered but never fully possessed. Despite Catherine’s claim that ‘No lofty theme shall now my pen employ’, her poem left me with a sense of awe, standing in the presence of something greater than myself. Some, like Catherine, might trace from nature ‘up to nature’s God’. For others ‘pure nature’ might their ‘active mind employ’ in deep awareness of the great mystery of the Great Forest. Catherine displays a spiritual alignment with her Forest; and her poem can awaken our Forest spirituality. Catherine provides more than snapshot postcard of a forest. Her relationship to ‘Dean’s ancient forest’ is appreciative, personal, and life-sustaining. Today, Catherine would no doubt abhor contemporary attempts to privatise, marketize or sell off the Forest of Dean. She would reject reducing the Forest’s magnificence to mere economic coin. Catherine, unquestionably a potential dedicated recruit for the ‘Hands off our Forest’ movement, would consider such threats to the Forest as originating in a mindset which makes no sense, has no soul, a modern-day ‘tyranny’. As Catherine Drew’s great poem becomes more widely known, it will deservedly take a bigger place in – and help to nurture - the Forest consciousness of future generations. Steven Carter, 2021 There was nothing out of the ordinary about a birth that took place on this day (17th May) 1935. The mother and father were living with her parents (not uncommon at the time), and so cramped were conditions that the birth took place at a neighbour’s house. The child was born at Brick House in Joyford on the edge of Berry Hill in the Forest of Dean. There was little that was remarkable either about the child as he grew up, playing in the woods, watching his grandfather in the village silver band and his mum and dad regularly doing a musical ‘turn’ at the local club. But he did well at school, and academic success for this son of a Forest coal miner would lead to a world of possibilities. After National Service he was off to New College Oxford where he plunged wholeheartedly into student life – taking part in drama productions and becoming editor of the prestigious student newspaper The Isis. The old pre-War class barriers were beginning to breakdown, and more opportunities were opening up. So, what would this young man do with his ‘shiny new degree’? We remember Dennis Potter today for his remarkable career in television, and perhaps here in the Forest of Dean most of all for his dramas Pennies from Heaven (1978), The Singing Detective (1986), and Cold Lazarus (1996) all featuring locally shot scenes (as well as local extras). There was the earlier – and for some, controversial – Wednesday Play A Beast with Two Backs (1968) much of which was also shot on location in the Forest. Television was Potter’s true passion and he had a huge impact on the development of television drama in particular. But his talents and interests were by no means limited to that one medium. He was a prolific journalist too (see The Art of Invective: selected non-fiction 1953-94, published in 2015), screenwriter for cinema, playwright for the stage, producer and director, cultural commentator, and even at one point stood for Parliament. And of particular interest for us at Reading the Forest, he was an author too. He wrote his first book, The Glittering Coffin (1960), whilst still at university. It was a ‘state of the nation’ work commenting on the society and politics of the time. It was highly personal in places with Potter writing in some detail (though briefly) about the Forest of Dean by way of example. At one point he admits, ‘I cannot hope to convey all that has happened in this district, but intend to produce a detailed study of the breakdown of a distinct regional identity at some future date’ (p44).  In 1962 his second book, The Changing Forest was published, and in some ways, it was indeed simply an expansion of those few paragraphs he’d written about the Forest in A Glittering Coffin. It was also though a more crafted and controlled expansion of the themes he’d touched on his BBC television documentary Between Two Rivers (1960). His first major piece of television work (he’d already appeared briefly in the documentary Does Class Matter whilst still a student and had worked on Panorama as a BBC trainee) that he wrote and presented, had upset many people in the Forest (though not all) who saw it. The opening half in particular saw Potter appearing to criticise his family and friends in the Forest, before later in the programme admitting he’d now changed his thinking and could now see the vitality and value of the Forest’s community and culture. In his book, The Changing Forest, Potter had the space, and the control over content, to express some of the detail and nuance that he wasn’t able to in the television format of Between Two Rivers. In the book (that shares a great deal with the programme) he spends more time with people and explores themes at greater length and in more detail. Potter as author is able to order and shape both evidence and argument in a way that he simply couldn’t in the television documentary. Potter’s developing skills as a journalist are clearly evident in The Changing Forest, but his authorship, just as in his work for television, would soon turn towards fiction-writing – art the better form, he realised, for telling truth. In all Potter would write four novels, and like his television dramas, they are often complex and challenging. As a young man he’d begun working on a novel, The Country Boy, though he never finished it. The various manuscripts of it are today housed in the Potter Archive at the Dean Heritage Centre (available to view on request). A few lines stand out as particularly poignant to those of us who know the Forest of Dean well. The young protagonist, David, is moved away from the Forest of Dean and is at a city-centre school in Fulham (just as Potter had). The other children refer to him as ‘the country boy’ because of his speech, but he finds it: ‘impossible to explain, he came from a hilly, green and lovely certainly, yet coalmining part of England, on the border of Wales. The Forest, the land on its own. Not just “the country”’ (for further details and analysis of this work see Carpenter, 1998, p86-88). There other scenes in the unfinished story that reappear nearly thirty years later in The Singing Detective, just as in a similar fashion the novels that he did complete and publish would inspire - or be inspired by - some of his other television work.  Potter’s first published novel was Hide and Seek (1973). Arguably a masterpiece of post-modern literature, the book plays to great effect with the novel form and the whole concept of the omnipotent author. Reading this challenging and exciting work it becomes clear that several of its ideas also made their way into The Singing Detective, (and later into Karaoke, 1996). The blurring of boundaries between author, protagonist and text, are particularly striking, as is one scene in particular, featuring a psychiatric consultation, all of which reappear in his television drama. Like much of Potter’s television work, the novel features seemingly biographical elements. It’s protagonist, Daniel Field, like Potter, went to Oxford, and he grew up in the Forest of Dean; the narrator in the book suffers from the same devastating skin disease as Potter; and Potter is known to at one point have had an appointment with a London psychiatrist. But as Potter would often explain, a writer’s experiences are merely the raw material he draws on and reshapes rather than a literal retelling of biographical incidents. As his biographer Humphrey Carpenter wrote, Potter’s message in this complex and tricky novel seems to be aimed at any future biographers: ‘I have been playing hide-and-seek with you. You think you are writing my life, but I am leaning over your shoulder, writing it for you. You, even you, are a character in my story. I can manipulate you too’ (Dennis Potter: The Authorized Biography, 1998, p291).  Potter's next novel, Pennies from Heaven (1981), was a far more straightforward work. After his 1978 BBC television serial, memorably featuring actors ‘lip synching’ to popular songs of the 1920s and 30s, and scenes filmed in the Forest of Dean, Potter had adapted the script for an MGM film released in 1981. Around the same time he turned the now USA-located narrative into a novel, the main challenge being that of conveying the same ideas without the musical elements of the film and television versions.  Ticket to Ride (1986) saw a return by Potter to previous form regarding his novel writing. Much like Hide and Seek, this novel was again dealing with themes of male sexual desire, breakdown, and the seemingly fractured self. The book opens as the protagonist suffers amnesia on a train as it arrives into Paddington Station, a moment of catastrophe that triggers a seeming division of John Buck, and the introduction of his internal ‘secret friend’. Potter is said to have written it in a burst of creative energy over 60 days, whilst also working on drafts of The Singing Detective screenplay (Carpenter, p446). The book was well received by the (literary) critics and was even considered as an entry for the Booker Prize (John Cook, Dennis Potter: A Life on Screen, 1995, p208). Again, there were elements in this novel that relate to some of his previous television plays. He went on to adapt it for the screen becoming the film Secret Friends (1991) starring Alan Bates and Gina Bellman, a film Potter himself directed.  He would go on to adapt his next novel Blackeyes (1987) also for the screen, this time as a four-part television drama of the same name broadcast on BBC2 in 1989. The TV adaptation starred Gina Bellman as a model and niece of an ageing writer (who in the television version also narrates her story). Potter dedicated the book to his daughters (Sarah and Jane, in their twenties at the time), and in it he addresses how advertising - culture more widely – commodifies and objectifies women’s bodies. He later explained how this was by extension a comment on broader culture and society. But what was perhaps safer territory to explore within a novel made for a far more problematic and controversial television outing, inducing criticism for what many saw as its own objectification of women. In the novel Potter again addresses the issue of ‘authorship’ through both the character of her uncle, himself a writer who seeks to exploit his niece’s experiences in his own work, and the ‘author’ of the novel we are reading, himself another character, ‘Jeff’, in the book (Cook, p261). Potter saw television as a means of communication that cut through the old class barriers that divided the audience of ‘high art’ (high-brow literature, fine art, opera etc.) from that of the ‘popular’ (pop music, variety entertainment, etc.). Television offered the opportunity to speak to all parts of society at the same time and Potter seized it. His feelings towards the novel as a form were more ambivalent. On the one hand he felt that writing a novel gave him ‘a certain freedom and relief’ from the demands of writing for the screen, whilst at the same time he believed that the novel as a contemporary form of writing ‘is almost dead’ (Potter On Potter, 1994, p127).

If the only work Dennis Potter had ever produced were his four novels he would surely demand our attention, and in the Forest of Dean some pride in his achievements. The fact that they represent the merest tiny fraction of his creative output is instead remarkable (see W. Stephen Gilbert's Fight & Kick & Bite: The Life and Work of Dennis Potter, 1995 for an excellent list of all of Potter's work). Yes, Potter will rightly be remembered and celebrated for his contribution to television. In the Forest of Dean in particular he will be remembered for the plays that saw the exciting world of television production set up shop (temporarily at least) in the neighbourhood. Of his books, if at all, it is his record and analysis of the area in the 1960s, The Changing Forest that continues to resonate to this day. But, whether in the Forest of Dean or anywhere else in the world, despite Potter’s own thoughts on the novel, pick up one his books for a change, and marvel at the genius of this sorely missed fine mind and creative talent!

Local history researcher Steven Carter recently came across a fascinating publication from the early nineteenth century. A Brief and Authentic Statement (1818) by the Reverend Payler Matthew Procter offers some fascinating insights into the Forest of Dean at the time, and for Steven in particular has resonated with his own own family history.

Now a retired teacher, Steven attended Lydney Grammar School in 1970s. Steven says, ‘My father is a true-born Forester, like his father, who was a life-saving hero of the 1949 Waterloo Colliery flooding. My Grandmother Cooper’s fascinating family history goes back hundreds of years at Berry Hill. Exploring the context for these roots and especially interviewing former Waterloo Colliery workers has made me a local history enthusiast. The Forest has a most fascinating history.’ Steven recently put on exhibitions about the Waterloo Colliery flooding at Hopewell Colliery and the Dean Heritage Centre. He has also written articles about the Colliery, the Mitcheldean industrialist and philanthropist Timothy Bennett (1804-61), and the 1861 Speech House Murder. He continues to be interested in anything connected to Waterloo Colliery. At the moment he is also investigating the history of the song 'The Jovial Foresters' and, how Edward Protheroe used slavery wealth to develop Forest tramroads, ironworks and collieries. REV. PROCTER'S BRIEF AND AUTHENTIC STATEMENT (1818) In The Changing Forest (1962), Dennis Potter laments pit closures and the ‘decline of the distinctive Forest culture’ of his childhood. He attributes the erosion of traditional ways to the onslaught of mass media and consumerism’s ‘newer, brighter, corroding uniformity’ (p10, 132) Reverend Procter’s Brief and Authentic Statement (1818) reveals a social and cultural revolution in the opening decades of the nineteenth century, comparable to and perhaps more fundamental than Potter’s. Procter narrates how the Anglican Church and an associated school became established at Berry Hill, and in doing so he incidentally provides glimpses of an older, more original Forest culture. Procter’s memoir swings through many forms, from simple narration, to sermon, theological tract and proof texts, to ecclesiastical and even salvation history; all helpful for understanding his Anglican perspective. For me, however, with my Grandmother’s Cooper ancestors among those earliest Berry Hill folk, of particular interest are those glimpses of the Forest community before the Church held sway. This old Forest culture was about to undergo profound change, as the outside influences of Church, Crown and Capitalists penetrated the Dean and transformed its inhabitants’ lives. Where some talk of ‘improvements’, others might say ‘dispossession’. As Chris Fisher showed in Market Capitalism: The Forest of Dean Colliers 1788-1888 (1981), market capitalism replaced customary rights and most independent miners became wage labourers. With Procter we catch the beginnings of this process, with important insights into the ‘Before’. Background Saxon and Norman kings had preserved the Forest as a royal hunting ground, but in later centuries the Crown became more interested in exploiting its resources, especially the iron, coal, stone and timber. Freeminers in small-scale operations, other Forest workers and local entrepreneurs, and the destitute and marginalised, settled inside the boundary whenever the authorities were weak. Each time the Crown regained strength, their crude cabins would be dismantled and squatters removed. In the late eighteenth century, however, the Deputy Surveyor responsible for the Forest reported that he had to desist from pulling down cottages, fences and inclosures because the encroachers’ repeated insults and threats made him fear for his life and property. By 1788 over 2,000 cottagers were established in 1,398 acres, with 589 makeshift cabins, many looking ‘too miserable for human occupation’, but others of stone or brick-built (By the 1830s the houses grew to 1462, with 2108 acres, until the Dean Forest [Encroachments] Act of 1838 allowed the older encroachments and prohibited further ones. In Warren James and the Forest of Dean Riots (1986) (p8-11) Forest author and historian Ralph Antis described this world, between the Severn and the Wye, cut off from mainstream English social and economic life: "the geographical isolation of the foresters… was compounded by [their work]. Miners everywhere form closed communities, but… their isolation was increased by their absolute refusal to allow anyone from outside the Hundred of St Briavels to join [their mining…] They call such outsiders ‘foreigners’". This wild country’s dark and frightening paths and threatening inhabitants deterred strangers. Writers before 1820, educated and well-to-do outsiders, agreed about the Foresters’ ‘wildness and lawlessness’; and showed little sympathy for their hard lives. Nevertheless, the Mine Law Court documents suggest a community centred around responsible freeminers, with a very sober, intelligent and orderly approach to solving their problems. Anstis concludes that the Foresters could be tough, touchy and fiercely independent - such that governments tended to leave them alone -, until the Crown’s increasing economic development and efficient management of the Dean confronted the Foresters with a challenge that would produce the biggest change in their way of life that they had ever known, provoking the Warren James riots and further government attempts to rationalise and control the Forest. Eventually, in the 1830s, the Dean Forest Commission and ensuing legislation imposed a new settlement on the Forest. The continued presence of sheep roaming the Forest and Freeminers underground, however, are modern day reminders that the Foreigners’ victory was not total. The Berry Hill Mission In 1803 Rev. Procter became Vicar of Newland. His interaction with the extra-Parochial Foresters was at first limited to visiting the sick and baptising babies. When Procter was to preach at Coleford Chapel, curiosity attracted some of the colliers and reports from these brought Freeminer Thomas Morgan. After hearing Procter’s preaching, Thomas became agitated in his soul and asked Rev. Procter to visit his home (next to the Church’s future location, that became the vicarage), where in deep conversation they discussed the fate of his soul. Thomas requested the Reverend to return next week, and if some friends and relatives could join them. Next Thursday Rev. Procter was surprised to discover a house so packed that he could hardly open the door to get in. Rev. Procter kept up these Thursday evening lectures for the coming years and his audience were unfailingly attentive. With benevolent intentions, a warm sympathy and prolonged effort, the good Reverend worked to prepare ‘these scattered people… for the Lord’ (p11). 'The Forest being extraparochial, it should be understood that the inhabitants have no right or power to command the services of any clergyman. A cold determination to do what is generally termed a benevolent act first induced me to go there. I saw nothing of them on the sabbath-day. The church was only used by them as a matter of course and necessity: indeed a general opinion prevailed that they had no right to accommodation, and a forester was seldom seen in the aisle' Procter admits also to a motive from ecclesiastical politics; to capture the Foresters before any Dissenter mission could. We can see that not everyone at Berry Hill welcomed these visits. This new way of life split the village. We can appreciate the sadness for Thomas’s friend who called on him to remember their good times together and re-join his former ways, but Thomas said their only togetherness could be for his former friend to stand where Thomas stood. Local curate and Forest historian the Reverend Nicholls' later comments (The Personalities of the Forest of Dean, 1863, p165) reveal the strong feelings aroused: 'These journeys into the Forest were not altogether free from danger. The old party did not like their sports to be interrupted. Until all fear from violence from them ceased, some portion of the congregation used to attend Mr Procter over the bounds of the Forest, after his Evening Lecture'. In this ‘culture war’ that split the village, ‘the old party’ might feel there was more at stake than interrupted sports. A new division was created and the community’s old ways were not surrendered without resistance. Thomas had the vision for a church and a school at Berry Hill and from his own generosity and effort, local contributions and two public appeals, these were established. Later legislation after the Dean Forest Commission incorporated the Forest into the Anglican parish system. Procter wrote his Memoir to help cover a debt of £950 that he had incurred by a technical fault when transferring property to set up the Church. His friends suggested the profits from this pamphlet could help pay off that heavy debt. Generations of my Grandmother Cooper’s ancestors attended the Church and many are buried in the graveyard behind. My special interest in Procter’s Brief and Authentic Statement, however, is not with any triumph of the Gospel, though it influenced generations of my ancestors’ worship and education. My Grandmother inherited a strong commitment to keeping Sunday special, and my Dad and his siblings attended the school and played on the triangle of grass outside. Since my own ancestors were among these early settlers at such evocative locations as Shortstanding, Joyford, Berry Hill and Hillersland, before ‘Christchurch’ was conceived, I have a special interest in the occasional glimpse Procter provides of their early Forest culture. Despite his churchman’s view of the Foresters, the much-loved Reverend provides direct views of his parishioners, including insights into their lives and Forest culture before the Established Church became an influential force in their community. The Older Forest Culture Although Procter criticises some Forest ways, his remarks also provide occasional perceptive insights into their culture. Procter’s account describes several aspects of Forest culture and life around Berry Hill from 1804 and earlier. ‘They are a people of themselves, of peculiar habits, tenacious in their dispositions, and from an idea, unfortunately too just, that the neighbouring parishes look upon them in an inferior point of view’ (p28). Based on ‘visiting of the sick’ and ‘baptizing of the children’, Rev Procter’s first impression – despite his feelings of sympathy and Christian love -‘was of the most unfavourable kind’, as he gained ‘knowledge of their condition, their lives and conversation, of which the latter were the most deplorable.’