rev. william wickenden

|

1796 - 1864

A prolific, popular author and occasional poet, he boasted Charles Dickens amongst his many readers. Born at Etloe on the banks of the River Severn he became friends with the vaccine pioneer Dr Edward Jenner who mentored him and later dubbed him 'The Bard of the Forest' - a title Wickenden would use in his books for the rest of his life. |

Much of what is known about William Wickenden's early (and indeed adult) life comes from his own writings, with only limited information from other independent and verifiable sources - indeed many later commentaries about Wickenden in themselves rely on his own writings as source material. Even within his works there are certain inconsistencies in his self-reporting, which means information needs to be viewed and certainly interpreted with some caution.

EARLY LIFE & family

William Wickenden was born in 1796 at Etloe, Gloucestershire, and was baptised on 6th April. He was the youngest but-one of ten children (six sisters and three brothers). His father John had married Ann Stephens at Lydney in 1777 and the couple farmed together at Etloe, their first child, John being born in 1778, their last child, Letitia being born in 1797. In 1810 when William was 14 years old his father died, aged 59 and was buried at Awre. John died 'intestate' and Gloucestershire Record Office holds an attestation from Ann dated 7th July 1810. This confirmed that she was his lawful widow, such that his goods and chattels could legally pass to her.

In many of his books William includes details of his childhood. He describes occasional periods of ill health which may be precursors of the later and more significant health issues which were to blight his adult life. His accounts include descriptions of incidents of high drama where he says his life had been in great danger, for example two potential drowning incidents in the River Severn , one of which was linked to a visit to Dr Jenner. Wickenden claims that, following his father’s death, he became largely responsible for the day to day running of the family farm. It is however worth noting that he was a younger son so more probably may have been working under the direction of an older brother. In the 1841 census William is listed as domicile with one of his elder brothers, Henry, a farmer at Etloe.

In many of his books William includes details of his childhood. He describes occasional periods of ill health which may be precursors of the later and more significant health issues which were to blight his adult life. His accounts include descriptions of incidents of high drama where he says his life had been in great danger, for example two potential drowning incidents in the River Severn , one of which was linked to a visit to Dr Jenner. Wickenden claims that, following his father’s death, he became largely responsible for the day to day running of the family farm. It is however worth noting that he was a younger son so more probably may have been working under the direction of an older brother. In the 1841 census William is listed as domicile with one of his elder brothers, Henry, a farmer at Etloe.

education

William is thought to have attended a local day-school, possibly at near-by Blakeney, or perhaps at Berkley on the opposite side of the River Severn at the time accessible by ferry (Adams, 2016, p9). In his 2016 book on Wickenden, author David Adams suggests that the private tutor Wickenden says he received lessons from was most likely William Gardiner in Lydney, himself an author.

Wickenden’s desire to gain an education broader than that available to him in the Forest led to him aspiring to attend Cambridge University. He was to write that, prior to entry to the University he lacked much of the knowledge required of him, for example in regard of Mathematics and Latin. He says he 'crammed’ on the areas of deficit, and was successful in gaining entry into St John’s College Cambridge in 1821. Wickenden’s limited funds meant he entered the university as a 'sizar'. Typically this was someone who received support in the form of lower fees, lodgings, or meals in return for taking on a defined role, for example acting as a servant to other students. For whatever reason Wickenden experienced a degree of ill health whilst at University, and did not gain the standard of degree to which he had aspired. He did however attain a BA and was ordained as a minister in 1825 (that date given by Wickenden in his own auto-biographical account).

Wickenden’s desire to gain an education broader than that available to him in the Forest led to him aspiring to attend Cambridge University. He was to write that, prior to entry to the University he lacked much of the knowledge required of him, for example in regard of Mathematics and Latin. He says he 'crammed’ on the areas of deficit, and was successful in gaining entry into St John’s College Cambridge in 1821. Wickenden’s limited funds meant he entered the university as a 'sizar'. Typically this was someone who received support in the form of lower fees, lodgings, or meals in return for taking on a defined role, for example acting as a servant to other students. For whatever reason Wickenden experienced a degree of ill health whilst at University, and did not gain the standard of degree to which he had aspired. He did however attain a BA and was ordained as a minister in 1825 (that date given by Wickenden in his own auto-biographical account).

DR EDWARD JENNER

|

Edward Jenner lived on the opposite side of the Rover Severn from Etloe at Berkley. The large tidal range of the river meant that, although potential dangerous, it could be crossed on foot at low tide. Jenner was a pioneer of the smallpox vaccine but was also a keen amateur poet. Written in 1850, Wickenden’s book Some Remarkable Passages in the life of William Wickenden, included a reprint of two letters he reportedly sent to Dr Jenner in 1816, when he would have been 20. In the letter he describes the locality of his home, and the Forest:

|

The Forest Scenery is of a dark and gloomy character. A succession of undulating hills, divided by abrupt ravines covered with holly trees and furze bushes [...] It is only in those parts of the Forest looking upon the river Severn , where the scenery is so surpassingly beautiful.

Wickenden describes having met and corresponded with Edward Jenner for some time, with Jenner offering encouragement to him (a young man), as he began to write, and later publish, publish both prose and poetry. He reports that Jenner introduced him to other ‘literary figures’ of the day and that further meetings ensued. His first published work was The Rustics Lay and Other Poems, of 1817 when he was only 20 or 21 years old. He dedicated it to Dr. Jenner. Wickenden claims that is was Dr. Jenner who first bestowed on him the soubriquet of ‘Bard of the Forest’ – an appellation he continued to use throughout his lifetime.

The date of May 1818 is specifically mentioned for one visit to Dr Jenner, with Wickenden returning on foot across the River Severn, when he was caught by the incoming Bore (tide). He describes a fight for survival, culminating in a rescue by people who had seen his ‘life or death race’ against the tide. His 1851 work Poems and Tales, with an Autobiographical Sketch of his early life, again includes reference to Jenner’s early interest in and support of him. One of Wickenden’s later friends and supporters, Henry Jeffs of Gloucester, wrote in a letter to The Citizen newspaper in 1887 that Jenner had ‘assisted’ Wickenden’s attendance at Cambridge, implying that this was in the form of financial assistance.

The date of May 1818 is specifically mentioned for one visit to Dr Jenner, with Wickenden returning on foot across the River Severn, when he was caught by the incoming Bore (tide). He describes a fight for survival, culminating in a rescue by people who had seen his ‘life or death race’ against the tide. His 1851 work Poems and Tales, with an Autobiographical Sketch of his early life, again includes reference to Jenner’s early interest in and support of him. One of Wickenden’s later friends and supporters, Henry Jeffs of Gloucester, wrote in a letter to The Citizen newspaper in 1887 that Jenner had ‘assisted’ Wickenden’s attendance at Cambridge, implying that this was in the form of financial assistance.

HIS ROLE AS A curateWilliam Wickenden held curacies in a number of locations, including one at Mudford in Somerset, and another at Lassington, a parish in Gloucestershire. He makes reference to an ‘ill judged’ attachment formed whilst serving as a curate, which was not acceptable to those in authority. Breaking off the relationship appears, in his view, to have been the trigger for a further setback to his health – this time one which was to blight his ability to fulfil his role as a clergyman, as he lost his voice. It is unclear wether or not his voice loss was permanent or intermittent. Given the supposed emotional triggers often linked to Wickenden’s ill health, it may be the case that the voice problems were functional in origin. A definition of such a disorder is as follows: ‘A functional disorder means the physical structure is normal, but the vocal mechanism is being used improperly or inefficiently. A final category of voice disorder is the psychogenic disorder, in which a poor voice quality becomes a symbolic, or outward, manifestation of some unresolved psychological conflict’ (www.lionsvoiceclinic.umn.edu )

For whatever reason, never fully able to resume a preaching role, Wickenden continued to write and to self-publish his works, primarily funded through people subscribing in advance and receiving one or more copy on publication. Many volumes of Wickenden’s prolific works contain a list of all subscribers. Following the deterioration of his health, from time to time, Wickenden’s supporters attempted to raise funds on his behalf. The vicar of Awre, J. H. Malpas placed an advert in the press, during a period when Wickenden was living back at the family home, attesting to Wickenden’s illness and resultant need to ‘subsist on charitable donations’ being genuine. Donations mentioned in this report include sums from the Lord Archbishop of Canterbury and the Lord Bishop of London, amongst others. in Dickens' Household wordsIn 1851 Wickenden had a short story published in the weekly magazine edited by author Charles Dickens. The story was titled 'A Tale of the Forest of Dean' (Household Words, 1851, Volume 3, pp461-464) |

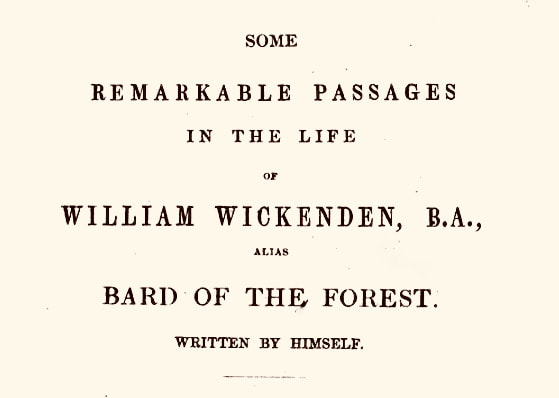

booksThe Rustic’s Lay and other poems (1817) Self-published, dedicated to Dr Jenner. A second edition published 1823, a third edition in 1827 (see below), a fourth edition in 1851 and a fifth and final edition in 1859. (Gloucester Journal 1872, p7) Count Glarus of Switzerland (1819) Self-published, again dedicated to Dr Jenner. Reviewed in two magazines – Gentleman’s Magazine and Monthly Magazine. Bleddyn, A Welsh National Tale (1821) Reviewed in the Cambro – Briton vol ii p46. Prose and Poetry by The Bard of the Forest (1825) Self Published (through subscription) Printed by Harwood and Hill, Bridge Street, Cambridge. Poems by the Bard of the Forest (1827) Printed by Harker and Penny, Mercury Office, Sherborne. Adventures in Circassia (1847) Wickenden dedicated this work to Charles Dickens. A Sequel to Adventures in Circassia (1848) Slee and Sons, Marshall Street, Golden Square A Queer Book (1850) Some Remarkable Passages in the life of William Wickenden B.A. Bard of the Forest (1850) Self-published, Printed by W Fallowfield Slee, 47 Marshall Street, Golden Square, London Poems and Tales, with an Autobiographical Sketch of his early life Hall (1851) Virtue and Co, Paternoster Row, London The Hunchback’s Chest (1852) Hall, Virtue and Co, London Reginald (1852) Hall, Virtue and Co, London Another Queer Book (1853) London, Thomas H Rees, Alpine Chambers, Paternoster Row Adventures before Sebastapool (1855) Revelations of a Poor Curate (1855) Adventures of Frank Ogilvy (1855) A. Hall, Virtue and Co., Paternoster Row, London |

later life

He lived in a variety of locations, sometimes in or around the Forest of Dean, at other times further afield. In the 1841 census Wickenden was living in Etloe with his brother Henry, who was roughly 10 years his senior. By the 1851 census he had relocated to London and was in lodgings at 8 Duke Street, Kensington, his landlord being by occupation a writer and painter. By the early 1860s further ill health led to him being admitted for surgery, which he did not survive. He died on 6th Feb 1864 at the London Hospital and was buried on 13th February 1864 at the City of London and Tower Hamlets Cemeteries (Henry Jeffs later stated in a letter to The Citizen in 1887 that the interment, which he attended, was at Bow Cemetery). Subsequently, obituaries to the ‘Bard of the Forest’ appeared in a number of newspapers, including The Gloucester Journal (Feb 29th 1864, p3) which cites several of his earliest publications as being work of ‘undoubted genius’ while further commenting upon certain ‘eccentricity of conduct’ having developed in his later life, such that: ‘Although of late years in comfortable and independent circumstances, he laboured under the hallucination that he was in a state of poverty, and appeals had privately been made by him to that effect’.

One of the executors of Wickenden’s will was Henry Jeffs, of Gloucester. Jeffs got to know Wickenden in the latter part of this life. Jeffs had a great regard for him and had a large collection of Wickenden's works which he states that he gave to a cottage library. Over twenty years after Wickenden’s death Jeffs wrote a number of letters to The Gloucester Citizen in response to the publication of his poem 'The Lassington Oak'. One such letter gives a level of insight into Wickenden’s death and will, although as it was written over twenty years after the event, the specifics must be viewed with some caution.

‘The night before the operation he made his will, and left £100 to the porter of the hospital and several thousands of pounds to nephews and other relatives. The body was [...] removed to the undertaker’s shop [...] The funeral was a very matter of fact sort of thing [...] There being four other funerals the ceremony was somewhat hurried [...] the grave is without the recognition of a head stone to this day. Such was the end of the Bard of the Forest’

(The Citizen, Nov 29th 1887, p3)

One of the executors of Wickenden’s will was Henry Jeffs, of Gloucester. Jeffs got to know Wickenden in the latter part of this life. Jeffs had a great regard for him and had a large collection of Wickenden's works which he states that he gave to a cottage library. Over twenty years after Wickenden’s death Jeffs wrote a number of letters to The Gloucester Citizen in response to the publication of his poem 'The Lassington Oak'. One such letter gives a level of insight into Wickenden’s death and will, although as it was written over twenty years after the event, the specifics must be viewed with some caution.

‘The night before the operation he made his will, and left £100 to the porter of the hospital and several thousands of pounds to nephews and other relatives. The body was [...] removed to the undertaker’s shop [...] The funeral was a very matter of fact sort of thing [...] There being four other funerals the ceremony was somewhat hurried [...] the grave is without the recognition of a head stone to this day. Such was the end of the Bard of the Forest’

(The Citizen, Nov 29th 1887, p3)

his Published Works and their Reception

fact or fiction?From his youth onwards Wickenden favoured the use of the first person in the majority of his prose, this encompassing both work with an overtly autobiographical remit and more sensational / adventure based writing such as Adventures in Circassia (1847). While some works are clearly fiction, the boundaries between the two (fact and fiction) are not always clearly defined, such that even the most sensational adventures can appear to be an autobiographical account. This, given Wickenden’s undoubted health issues is clearly not the case. This confusion of fact and fiction is compounded by the protagonist in certain stories (including Adventures in Circassia) referring to himself as having been a clergyman and as a ‘Dean Forester’, this being a close parallel with Wickenden’s own history. Indeed, in A Sequel to Adventures in Circassia (1848) the author merges his persona and that of his hero even more, by referring to ‘The Bard of the Forest’ in the West being known as ‘Gherei the Anglo Circassian’ (the hero of the novel!) in the East, while a ‘conversation’, between ‘The Bard’ and a ‘Miss Scraggs’ which prefaces the novel includes the following dialogue:

Miss Scraggs: ‘then you mean to hassert that you have hactually travelled in Circassia, and that the Hadventures are not feigned?’ |

SOME SUBSCRIBERS TO HIS WORKHe had a very wide range of subscribers, from family members and local dignitaries, to fellow clergymen and respected authors.

Prose and Poetry by The Bard of the Forest (1825) Self published. Subscribers were informed in the volume that only one rather than several volumes was to be published! Subscribers included Miss Alice and Miss Letitia Wickenden (his sisters). Poems by the Bard of the Forest (1827) Self published. Subscribers included Charles Bathurst of Lydney Park, and many fellow clergymen. Some Remarkable Passages in the life of William Wickenden B.A. Bard of the Forest (1850) Subscribers included Sir M. H. Crawley-Boevey of Flaxley Abbey; M. A. Malpas, Vicar of Awre; Rev. H. Stebbing, of St James Chapel, Hampstead; Charles Dickens. |

HEALTH ISSUES AND RECEPTION IN THE PRESS

Many of his works contain a preface from the author. An example taken from The Adventures of Frank Ogilvy (1855), expressing his own views on his achievements, reflect on what had been a particularly productive period for the author:

‘Another work by the Bard of the Forest! [...] most assuredly it is not very often we see four distinct works, averaging four hundred and sixty pages, brought out in the course of a little more than eighteen months [...] all this was done by my own unassisted energy [...] I belong to no clique of writers [...] I stand isolated and alone’.

Wickenden mentions his frequent illnesses and repeated hospitalisations within some of the preface material. It is thus evident that the press of the day had reason to be aware of both Wickenden’s talents and his health issues. Shortly after publication of The Hunchback’s Chest (1852) a review in The Salisbury and Winchester Journal (28th Feb 1852, p.4) reads: ‘There is a degree of vigour and freshness about Mr. Wickenden’s writings that is charming [...] His language is generally expressive and often poetical [...] Debarred by a physical calamity from fulfilling the sacred duties of his profession, we should be glad to see Mr Wickenden placed comfortably in an honourable asylum, where [...] he might dedicate himself to the pursuits of literature, and achieve the reputation which is at once the hope and reward of the aspiring scholar’. However, as is still the case with modern authors, not all contemporary accounts appear to have recognised his talents, as in an opposing review of this same work: ‘Although prevented by physical incapacity from discharging the duties of (an ordained minister), we ask him seriously whether he cannot devote his time and talents to a better purpose then writing such tales..’. (Morning Advertiser, 23rd Dec 1851 p6)

Similarly disparaged in the press, later in the same year, was Reginald, which was ‘designed to illustrate the times of Queen Elizabeth’. The Bell’s Weekly Journal clearly does not feel the work met its intended remit: ‘How this gentleman could have written such an aimless work as ‘Reginald’ and conjured before his own mind such unnatural characters and events as it portrays, we are utterly at a loss to conceive’.

Heroic deeds undertaken by the hero abound within many stories, as in the following example, taken from the Sequel to Adventures in Circassia (page 4/5): ‘"Poor Sebastien is overboard", shouted several voices. Sebastien was an especial favourite of mine. He was a Mozambique lad, vigilant and faithful, so without reflecting that I could swim no more than a pound weight, I jumped overboard with the intention of rescuing him. Yes, I jumped overboard, through the yielding waters I went to an unknown depth – struggling and spluttering….’

Similarly disparaged in the press, later in the same year, was Reginald, which was ‘designed to illustrate the times of Queen Elizabeth’. The Bell’s Weekly Journal clearly does not feel the work met its intended remit: ‘How this gentleman could have written such an aimless work as ‘Reginald’ and conjured before his own mind such unnatural characters and events as it portrays, we are utterly at a loss to conceive’.

Heroic deeds undertaken by the hero abound within many stories, as in the following example, taken from the Sequel to Adventures in Circassia (page 4/5): ‘"Poor Sebastien is overboard", shouted several voices. Sebastien was an especial favourite of mine. He was a Mozambique lad, vigilant and faithful, so without reflecting that I could swim no more than a pound weight, I jumped overboard with the intention of rescuing him. Yes, I jumped overboard, through the yielding waters I went to an unknown depth – struggling and spluttering….’

WRITING ABOUT HIS EARLY LIFE IN THE FOREST OF DEAN

A number of Wickenden’s works include descriptions of his early life. Some Remarkable Passages in the life of William Wickenden B.A. (1847) includes recollections of the author’s childhood.

I often paint in my mind’s eye the white washed cottage [...] its fantastic garden with its formal clipt yew and box trees...

My advantages of birth were in no respect superior to those of other farmers’ sons. To tend the herds, to turn the furrow were the earliest lessons I received...

About half a mile (away) was a quiet, retired dell [...] in this pleasant and sweet place I spent many happy hours and composed many little rural poems.

Wickenden describes an incident which nearly claimed his life, and also may show the first indication of the health issues that were to plague his later life: 'About 12 years of age I nearly drowned (in the River Severn)…..so immersed that I did not perceive that the tide had completely enclosed me and cut off my retreat [...] my desperate efforts were finally crowned with success, and bleeding and exhausted with terror I attained my place of refuge [...] I was however laid up with a fever for several weeks and with difficulty recovered'.

Wickenden claims to have started an unsuccessful Day School in Berkeley in 1815, lodging with a landlady there. After the school closed, he resumed work at the farm, studying independently by night. In 1821 he self-published a second novel, Bleddyn, which was fairly well received, and brought in money. A letter from the young Wickenden, written from Etloe, to accompany an extract of this novel is published in The Cambro-Briton, 1820, vol ii, page 48.

Wickenden’s devotion to study and overall ambition thus led him to ‘cram’ and take the examinations that would allow him to gain entry to Cambridge University. He entered as a ‘sizar’ – this involving him acting as a servant to other students, in return for paying a lower rate of fees for his studies. His attendance at the University is confirmed by several sources including:

Wickenden claims to have started an unsuccessful Day School in Berkeley in 1815, lodging with a landlady there. After the school closed, he resumed work at the farm, studying independently by night. In 1821 he self-published a second novel, Bleddyn, which was fairly well received, and brought in money. A letter from the young Wickenden, written from Etloe, to accompany an extract of this novel is published in The Cambro-Briton, 1820, vol ii, page 48.

Wickenden’s devotion to study and overall ambition thus led him to ‘cram’ and take the examinations that would allow him to gain entry to Cambridge University. He entered as a ‘sizar’ – this involving him acting as a servant to other students, in return for paying a lower rate of fees for his studies. His attendance at the University is confirmed by several sources including:

- An entry in the Cambridge University Alumni 1261 – 1900 records states:‘Born 1797….sizar at St John’s, Cambridge, June 19, 1821, of Gloucestershire (n.b. the author himself gives a commencement date of 10th October 1821)

- Whilst at the University Wickenden wrote the poem Australasia, which had he entered as contender for Cambridge Prize Essay. He failed to win but the poem was subsequently to appear in some of his later publications including Prose and Poetry by The Bard of the Forest (1825).

Additional Sources

- Ancestry.co.uk, online

- British Newspaper Archive, online

- Severnside to Circassia: Being the Life & Works of the Remarkable Rev. William Wickenden of Etloe Bard of the Forest (2016) by David Adams. Yorkley A & E.

Thanks to volunteer Caroline Prosser-Lodge for her research and writing on this page.