Rev. h. g. NICHOLLS

EARLY LIFE

|

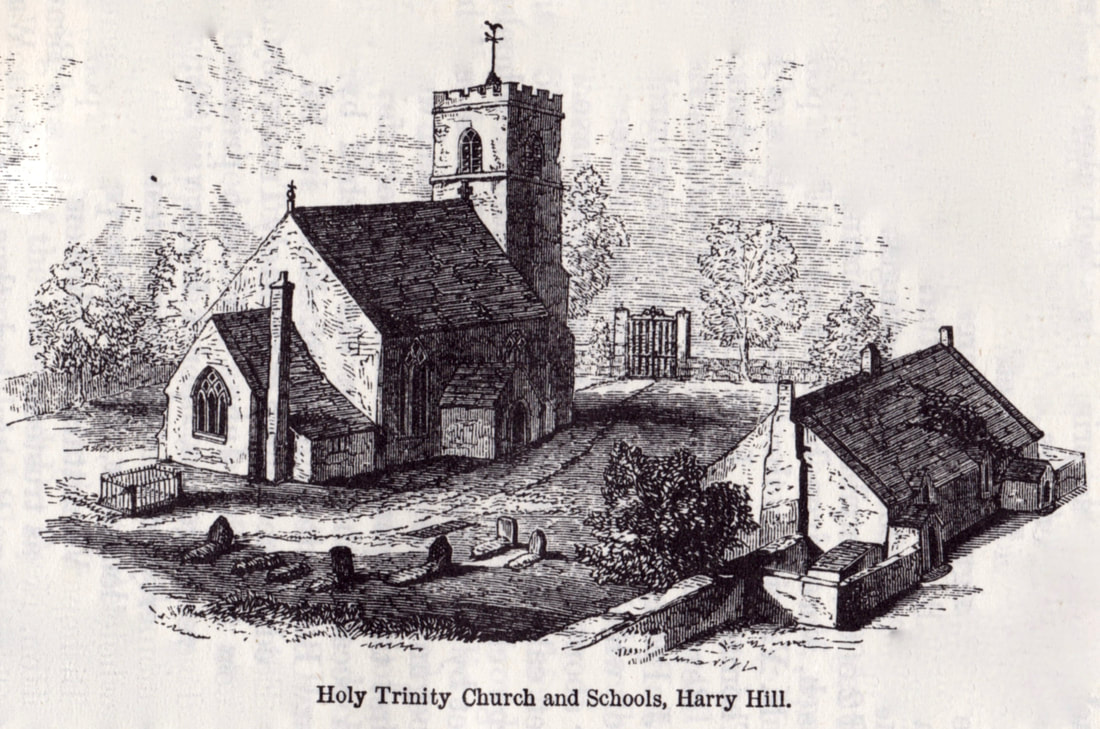

Henry George Nicholls was born on 10th January 1822, in Nottinghamshire. Baptised at Southwell (Minster) on 14th January 1822, Henry was the only son of Sir George Nichols and his wife Harriet. He had seven sisters, not all of whom survived to adulthood. Henry attended Rugby School, before going on to study at Trinity College, Cambridge, where he attained his B.A. in 1845 and his M.A. three years later. He was concurrently ordained in 1845, being appointed Perpetual Curate at Holy Trinity Church, Drybrook in December 1847.

|

BOOKSThe Forest of Dean: an historic and descriptive account (1858) The Personalities of the Forest of Dean (1863) Iron Making in the Olden Times: as instanced in the ancient mines, forges, and furnaces of the Forest of Dean (1866) |

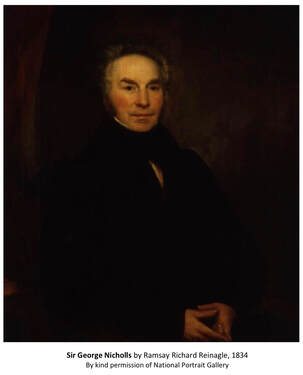

Henry's father

George Nichols was very closely involved with Poor Law reform, which contributed to the opening of vast workhouses throughout the country. These were seen as a last resort by the poor and it is interesting to speculate what impact growing up in a household so closely aligned with the planning and implementation of such reforms may have had on the young Henry. As a young man George had been employed in the navy of the Honourable East India Company. In 1815, his first command, the Lady Lushington, caught fire and was destroyed. Although totally exonerated, George left the navy after this incident to pursue an alternative career (Dictionary of National Biography: from the earliest times to 1900, Vol 1-22). George and his young family lived in various locations over the years, due to the changing nature of his work (whilst based in Gloucester George served as the Chairman of the company during the construction of the Gloucester and Berkeley Ship Canal). At the time of Henry’s birth George lived and worked in Southwell where he became deeply involved in local affairs. He was as an Overseer of the Poor during this time and was perceived as the instigator of a number of experiments regarding how best to ‘support’ the poor. A letter written to the press by George during this period makes his views plain:

“ The overseers must resolutely refuse all parochial aid, except relief to the aged, infirm and impotent. ......I wish to see the poor house looked to with dread by our labouring classes and the reproach of being an inmate of it passed down from father to son. Let the poor see and feel that their parish...is yet the hardest taskmaster and the most harsh and unkind friend they can apply to”

This description is consistent with the harsh regime of Victorian Workhouse life written about by Charles Dickens. When he retired from public life in 1851 George was created a life peer. When he died in March 1865, Henry was named as joint executor of his will, together with his (Henry’s) unmarried sister Elizabeth, and brother-in-law William Willink.

“ The overseers must resolutely refuse all parochial aid, except relief to the aged, infirm and impotent. ......I wish to see the poor house looked to with dread by our labouring classes and the reproach of being an inmate of it passed down from father to son. Let the poor see and feel that their parish...is yet the hardest taskmaster and the most harsh and unkind friend they can apply to”

This description is consistent with the harsh regime of Victorian Workhouse life written about by Charles Dickens. When he retired from public life in 1851 George was created a life peer. When he died in March 1865, Henry was named as joint executor of his will, together with his (Henry’s) unmarried sister Elizabeth, and brother-in-law William Willink.

MARRIAGE & FAMILY

Rev. Nicholls married on 17th August 1853, during his tenure in the Forest. His bride was his first cousin, Caroline Maria Nicholls. Caroline Maria was born in Madras, India, in December 1821, the daughter of Solomon and Charlotte Nicholls. The couple married in the bride’s home town, Tiverton, Somerset, the service being jointly conducted by the local vicar and Rev. James Davis, rector of Abenhall Church in the Forest of Dean. The couple went on to have several children: daughters Agnes Caroline (b. 1854), Emily Jane (b. 1856), George Maltby (b. 1858), Harriet Marianne (b. 1859), Charlotte Selina (b. 1861) and twin sons Henry Millett and Frederick William (b. June 1863). Frederick sadly died when an infant, at the age of 7 months. Most of the children were baptised, not by their father, but by the Rev. James Davis, rector of the nearby Abenhall Church. Due to Henry’s increasing health issues, the family left the Forest in 1866, thereafter living in London where they remained until after his untimely death, later settling as a family in Broadwater, Sussex. The children all married between 1876 and 1885. The newspaper reports of all their marriages made reference to their father as being ‘the late Rev. H. G. Nicholls’.

Two Incidents of Recourse to the Law

In 1850 a curious incident occurred in which a letter posted and registered by Rev. Nicholls, packed together with another registered item containing money, disappeared in transit from the local mail cart. The bag containing the items was found to be damaged. In subsequent days, Joseph Probert, the young man who had driven the cart, appeared to have a lot of money to spend. He was eventually arrested, found guilty of the theft and sentenced to transportation (Hereford Times, 17th August 1850, page 3-4). In 1861 George Price, a labourer, pleaded guilty to stealing 3 cheeses from the dairy of Rev H G Nicholls, together with the theft of a book from a Mr C Harding. Price was sentenced to 12 months hard labour. (Hereford Times, 17th August 1861, page 6).

In 1850 a curious incident occurred in which a letter posted and registered by Rev. Nicholls, packed together with another registered item containing money, disappeared in transit from the local mail cart. The bag containing the items was found to be damaged. In subsequent days, Joseph Probert, the young man who had driven the cart, appeared to have a lot of money to spend. He was eventually arrested, found guilty of the theft and sentenced to transportation (Hereford Times, 17th August 1850, page 3-4). In 1861 George Price, a labourer, pleaded guilty to stealing 3 cheeses from the dairy of Rev H G Nicholls, together with the theft of a book from a Mr C Harding. Price was sentenced to 12 months hard labour. (Hereford Times, 17th August 1861, page 6).

ministry in the forest

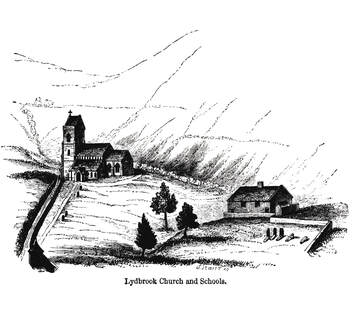

H. G. Nicholls was licensed as Perpetual Curate of the Holy Trinity Church in Drybrook in late December 1847 (Express, London, 18th December 1847, page 3). The post had become vacant on the death of Rev. H. Berkin, the previous incumbent. Berkin had, as early as the 1820s, overseen the building of a chapel, later to be used as a schoolroom, in Lynbrook. One of Rev. Nicholls’ earliest duties in post was to deliver a sermon there in August 1850 to mark the laying of a foundation stone for a new church to be built next to the chapel (Hereford Journal, 21st August 1850). Some 16 months later, in December 1851, Nicholls, together with the Rev. Edward Machen, led a service of consecration at the opening of the new church in Lynbrook. A chapter of Nicholls' first book describes the development of religion and education in the Forest, the churches and their congregations (as of 1858) being included in very considerable detail. He states that the church where he was incumbent, Holy Trinity, then had an average of 100 attendees at morning service, rising to 350 in the afternoon and around 120 at each of the two evening services (The Forest of Dean, Chapter X).

Friendly Societies

Allied with his clerical role, Henry was closely involved in the development of church run schools within the Forest and with the establishment of parochial Friendly Societies in and around the Forest. Friendly Societies had existed in the UK from as early as the late seventeenth century, and in August 1850 a Friendly Societies Bill was discussed in Parliament. The aim of the Societies was to benefit ‘the lower class of people’. Members paid into the Society with benefits made available in terms of ‘allowances in sickness, annuities in old age and during widowhood, payments at death, and endowments for children’. A newspaper report, reflecting on the local situation in the Forest of Dean, stated that ‘there is no place in which such a Society can be more useful, the casualties by sickness and death being very large, owing to the peculiar employment of the population’(Gloucester Journal, 14th September 1850, page 3). A number of individual Societies existed in the Forest around this time, based in local communities and often closely associated with the local church, though some were run through public houses. Nicholls was personally associated with several such Societies, including the Littledean Sick and Burial Club, the Plump Hill Benefit Society and Mr Smart’s Club, of Brierley. It is interesting to speculate to what degree Rev. Nicholls’ involvement with these societies may be a response to the only option that might otherwise have been available to the local community – entry to a Workhouse of the sort established through the work of his father and others.

Friendly Societies

Allied with his clerical role, Henry was closely involved in the development of church run schools within the Forest and with the establishment of parochial Friendly Societies in and around the Forest. Friendly Societies had existed in the UK from as early as the late seventeenth century, and in August 1850 a Friendly Societies Bill was discussed in Parliament. The aim of the Societies was to benefit ‘the lower class of people’. Members paid into the Society with benefits made available in terms of ‘allowances in sickness, annuities in old age and during widowhood, payments at death, and endowments for children’. A newspaper report, reflecting on the local situation in the Forest of Dean, stated that ‘there is no place in which such a Society can be more useful, the casualties by sickness and death being very large, owing to the peculiar employment of the population’(Gloucester Journal, 14th September 1850, page 3). A number of individual Societies existed in the Forest around this time, based in local communities and often closely associated with the local church, though some were run through public houses. Nicholls was personally associated with several such Societies, including the Littledean Sick and Burial Club, the Plump Hill Benefit Society and Mr Smart’s Club, of Brierley. It is interesting to speculate to what degree Rev. Nicholls’ involvement with these societies may be a response to the only option that might otherwise have been available to the local community – entry to a Workhouse of the sort established through the work of his father and others.

Schools

In the sphere of education, Rev. Nicholls describes both National School and church involvement in the construction of a first ‘Forest Day School for Boys and Girls’ opened in 1812. Further schools gradually emerged and Nicholls was himself later involved in the establishment of several Forest schools including those at Holy Trinity, Upper Lydbrook, Littledean Hill, Hawthorns (north of Drybrook and Ruardean Woodside (Mary Atkins, Reverend H G Nicholls, The Forest’s First Historian’ New Regard No. 23, 2008). March 1855 saw Nichols delivering the third of a course of lectures to schoolchildren in the schoolroom at Holy Trinity Church. His chosen topic was ‘hydrogen’ (Monmouthshire Beacon, 10th March 1855, page 8). Nicholls was the President of the Schoolmasters’ and Schoolmistresses’ Association for the Forest District(Monmouthshire Beacon, 11th July 1857, page 5). At the July 1857 meeting, in his address to the Association he spoke about the history of the Forest of Dean – a precursor perhaps of his first book, which was published the following year. The Association brought together teachers from church schools throughout the Forest – newspaper reports mentioning schools at the time in Parkend and Viney Hill as well as other locations. Meetings of the Association were usually held in the schoolroom of Holy Trinity Church.

Nicholls served as the Chairman of the local (Cinderford) branch of the British and Foreign Bible Society. The Parent Society at the time was supporting work in Ireland, France, Italy and Turkey.

By January 1857 Rev. Nicholls had started an ‘Improvement Society for the improvement of his flock’. The first speaker was Mr Jordan of Cinderford Colliery, on the subject of light. A newspaper report comments that the number of members at present ‘is but small’, but outlined Nicholls’ hope that more would soon avail themselves of its opportunities (Monmouthshire Beacon, 24th January 1857, page 7). A Holy Trinity band was formed in 1859, which practiced, with Nicholls support, in the schoolroom at Holy Trinity. Their first performance was at the Lodge of the Odd Fellows of Ruardean 18th anniversary. The band was praised for ‘their capital performances’ (Gloucester Journal, 16th July 1859, page 3).

In the sphere of education, Rev. Nicholls describes both National School and church involvement in the construction of a first ‘Forest Day School for Boys and Girls’ opened in 1812. Further schools gradually emerged and Nicholls was himself later involved in the establishment of several Forest schools including those at Holy Trinity, Upper Lydbrook, Littledean Hill, Hawthorns (north of Drybrook and Ruardean Woodside (Mary Atkins, Reverend H G Nicholls, The Forest’s First Historian’ New Regard No. 23, 2008). March 1855 saw Nichols delivering the third of a course of lectures to schoolchildren in the schoolroom at Holy Trinity Church. His chosen topic was ‘hydrogen’ (Monmouthshire Beacon, 10th March 1855, page 8). Nicholls was the President of the Schoolmasters’ and Schoolmistresses’ Association for the Forest District(Monmouthshire Beacon, 11th July 1857, page 5). At the July 1857 meeting, in his address to the Association he spoke about the history of the Forest of Dean – a precursor perhaps of his first book, which was published the following year. The Association brought together teachers from church schools throughout the Forest – newspaper reports mentioning schools at the time in Parkend and Viney Hill as well as other locations. Meetings of the Association were usually held in the schoolroom of Holy Trinity Church.

Nicholls served as the Chairman of the local (Cinderford) branch of the British and Foreign Bible Society. The Parent Society at the time was supporting work in Ireland, France, Italy and Turkey.

By January 1857 Rev. Nicholls had started an ‘Improvement Society for the improvement of his flock’. The first speaker was Mr Jordan of Cinderford Colliery, on the subject of light. A newspaper report comments that the number of members at present ‘is but small’, but outlined Nicholls’ hope that more would soon avail themselves of its opportunities (Monmouthshire Beacon, 24th January 1857, page 7). A Holy Trinity band was formed in 1859, which practiced, with Nicholls support, in the schoolroom at Holy Trinity. Their first performance was at the Lodge of the Odd Fellows of Ruardean 18th anniversary. The band was praised for ‘their capital performances’ (Gloucester Journal, 16th July 1859, page 3).

writing about the forest of dean

Most contemporary reports comment on the intimate personal knowledge of the area that Rev. Nicholls gained as a result of his time living and working in the Forest of Dean. During his tenure in Drybrook Nicholls penned three works about the Forest in which he had made his home, all with a primarily historical focus. The first comprised a detailed history of the Forest; the second took as its theme the people and personalities of the Forest; while the third honed in on one particular aspect of its industrial history – iron making. Had Nicholls not become ill, it is highly likely that more books would have followed. Nicholls makes detailed use of a variety of primary source material in his books, including State Papers, Forest Rolls etc. From such sources a high level of historical and factual accuracy can be assumed. In some instances he was reliant on materials made available to him, or by word of mouth, via notable people in the area (Edward Machen and Edward Protheroe are amongst those mentioned by name), and by less prominent local individuals. Other material is drawn from his own observations for example regarding the characteristics, legends and beliefs of the local population. Some degree of caution should perhaps be exercised when considering the more anecdotal material, as this would have been dependent upon the accurate recall or knowledge of his informant(s), in combination with his own interpretation of such information.

The first two volumes provide information regarding Nicholls' personal perceptions as to the personality and temperament of the local population, and some aspects of these traits he ascribes to the proximity of the area to Wales. Speaking of the Silurians, who are believed to have lived in the area, he states that, ‘their chief influences ...appear to have descended from the Welsh, with whom the foresters of the present day still seem closely to assimilate. Hence their somewhat impulsive temperament’.

Nicholls talks also of the geographical isolation of the area, which he considers to contribute again to the character of its inhabitants: 'For many generations an isolated and peculiar people, most of them are ignorant of the rest of the world, and have of course a correspondingly exaggerated idea of their own importance’ . Speaking of the mining community, he comments: 'One source of evil arises from the large ablutions which their working underground necessitates. The process...is not performed as privately as it might be, and the effect of this upon the moral perceptions of the people, huddled together in their small cottages, is very injurious’. He does, however, go on to express the wish that washhouses might be available at the pit heads to reduce the need for such domestic arrangements. It may be some of the Reverend’s expressed views contributed to a certain degree of local criticism of his works, (discussed below).

The first two volumes provide information regarding Nicholls' personal perceptions as to the personality and temperament of the local population, and some aspects of these traits he ascribes to the proximity of the area to Wales. Speaking of the Silurians, who are believed to have lived in the area, he states that, ‘their chief influences ...appear to have descended from the Welsh, with whom the foresters of the present day still seem closely to assimilate. Hence their somewhat impulsive temperament’.

Nicholls talks also of the geographical isolation of the area, which he considers to contribute again to the character of its inhabitants: 'For many generations an isolated and peculiar people, most of them are ignorant of the rest of the world, and have of course a correspondingly exaggerated idea of their own importance’ . Speaking of the mining community, he comments: 'One source of evil arises from the large ablutions which their working underground necessitates. The process...is not performed as privately as it might be, and the effect of this upon the moral perceptions of the people, huddled together in their small cottages, is very injurious’. He does, however, go on to express the wish that washhouses might be available at the pit heads to reduce the need for such domestic arrangements. It may be some of the Reverend’s expressed views contributed to a certain degree of local criticism of his works, (discussed below).

The Forest of Dean: an historical and descriptive account (1858)

A newspaper report at the time of publication of this first volume stated that ‘Until this volume appeared there existed no printed history of the Forest of Dean’ (Cheltenham Chronicle, 30th November 1858, page 3). Nicholls can then be viewed as the first historian of the Forest, (the title ascribed to him in an article written by Mary Atkins, which appeared in the journal of the Forest of Dean Local History Society, The New Regard, No.23, page 18-22).

The first several chapters of his book look at the history of the area across the period 1307 – 1858, while the remainder focuses in turn on specific themes: the inhabitants of the Forest; religion and education; roads and railways; Flaxley Abbey; deer and timber (and other flora and fauna); iron mines and workings; coal works and, finally, the geology of the area. A few years after its publication, in November 1863, Rev. Nicholls delivered a talk entitled simply ‘The Forest of Dean’, at the National School in Blakeney, in which he stated that (he): ‘came to the Forest a perfect stranger...knowing nothing of its history save a few things....(However).. he consulted a number of gentlemen residing in the neighbourhood, and set to work with all the information he could obtain, and succeeded in compiling a small volume’. In the talk, which was reported in very great detail, Nicholls summarised the history of the area and related a number of anecdotes and stories about it taken from the book (Gloucester Journal, 7th November 1863, page 6).

The book was a favourite of later Forest of Dean historian Cyril Hart (1913-2009) who prepared a re-issue of it (along with Iron Making in a single volume) in 1966. Hart wrote an introduction and additional notes for the new volume.

A newspaper report at the time of publication of this first volume stated that ‘Until this volume appeared there existed no printed history of the Forest of Dean’ (Cheltenham Chronicle, 30th November 1858, page 3). Nicholls can then be viewed as the first historian of the Forest, (the title ascribed to him in an article written by Mary Atkins, which appeared in the journal of the Forest of Dean Local History Society, The New Regard, No.23, page 18-22).

The first several chapters of his book look at the history of the area across the period 1307 – 1858, while the remainder focuses in turn on specific themes: the inhabitants of the Forest; religion and education; roads and railways; Flaxley Abbey; deer and timber (and other flora and fauna); iron mines and workings; coal works and, finally, the geology of the area. A few years after its publication, in November 1863, Rev. Nicholls delivered a talk entitled simply ‘The Forest of Dean’, at the National School in Blakeney, in which he stated that (he): ‘came to the Forest a perfect stranger...knowing nothing of its history save a few things....(However).. he consulted a number of gentlemen residing in the neighbourhood, and set to work with all the information he could obtain, and succeeded in compiling a small volume’. In the talk, which was reported in very great detail, Nicholls summarised the history of the area and related a number of anecdotes and stories about it taken from the book (Gloucester Journal, 7th November 1863, page 6).

The book was a favourite of later Forest of Dean historian Cyril Hart (1913-2009) who prepared a re-issue of it (along with Iron Making in a single volume) in 1966. Hart wrote an introduction and additional notes for the new volume.

The Personalities of the Forest of Dean (1863)

At the time of its publication it was described as ‘an appendix to his earlier “Historical and Descriptive Account of the Forest”' which itself was described as having ‘produced in the minds of many a desire for further information in regard of the families and individuals’ (Literary Times, 8th August 1863). The new book was perceived as constituting Nicholls’ response to this quest for additional information. It contained material about members of many notable families of the area, including the Boeveys of Flaxley Abbey, the Machens of English Bicknor and material related to his predecessor at Holy Trinity, Rev. Berkin. Alongside this he included material about the ‘everyday’ population of the Forest, their beliefs and superstitions. Reviewers at the time described this book as being ‘for the most part a collection of small biographies of the notabilities, lay and clerical, who have lived and laboured amongst the singular population of the Forest of Dean’ (Illustrated London News, 14th November 1863, page 18). One particular ‘anecdote’, in the form of a three way conversation, (Nine Eyes, First Collier and Second Collier) seemed to lead to some local controversy, both at the time of publication and beyond. This was due to the impression given to the reader regarding the mode of speech, superstitions and attitudes of the three protagonists. The item is entitled ‘The Haunted Pit’, and the story centres on a long-missing miner from Guardian by the name of ‘Get-it-to-go’. Unexplained noises came from a nearby pit, and a figure of a man was occasionally seen passing by the local cottages. Finally a decision was taken – the pit must be examined in the hope of discovering the cause – and perhaps establishing Get-it-to-go’s fate - once and for all. Sure enough the exploring party found the man’s remains in the pit and it was removed for burial. The basic story is augmented by a conversation (set prior to the discovery of the body) between two colliers and their friend Nine Eyes, who plan to walk to the pit to investigate the noises. It is written entirely in Rev. Nicholls interpretation of the local Forest dialect. During a discussion as to the probable haunting of the mine, Nine Eyes comments, ‘.Who knows but what Get-it-to-Go’s ghost is a working of it round to let us know that he aint be sarved aright, and that it wants to be looked into’. This book, this particular story, and indeed the author, were not universally loved. Writing to the Hereford Times in September 1863, soon after the book was published, one Joseph James of Ruardean Hill states: 'He has published a work calculated to insult and alienate his parishioners. The superstitions which he states are in existence everywhere are decidedly a mistake....’ The letter writer concludes – in what at first glance it appears to be a positive statement, but from what has gone before would appear to be anything but: - ‘The affection he has for his people may be imagined from the way in which he treats them; and the love his people have for him may be estimated from the number who attend when he officiates’. As late as 1880, some 13 years after his death, doubts about the accuracy of certain material within this book were still being expressed in the press. Commenting on information in the volume about one such family (the Kembles, possibly linked to the Siddon family of Lydbrook) a letter writer states ‘the (works) are of no small interest, but their accuracy must not be relied upon farther than Mr Nicholl’s personal knowledge and observation extended’ (Stroud Journal, 8thMay 1880, page 2-3).

At the time of its publication it was described as ‘an appendix to his earlier “Historical and Descriptive Account of the Forest”' which itself was described as having ‘produced in the minds of many a desire for further information in regard of the families and individuals’ (Literary Times, 8th August 1863). The new book was perceived as constituting Nicholls’ response to this quest for additional information. It contained material about members of many notable families of the area, including the Boeveys of Flaxley Abbey, the Machens of English Bicknor and material related to his predecessor at Holy Trinity, Rev. Berkin. Alongside this he included material about the ‘everyday’ population of the Forest, their beliefs and superstitions. Reviewers at the time described this book as being ‘for the most part a collection of small biographies of the notabilities, lay and clerical, who have lived and laboured amongst the singular population of the Forest of Dean’ (Illustrated London News, 14th November 1863, page 18). One particular ‘anecdote’, in the form of a three way conversation, (Nine Eyes, First Collier and Second Collier) seemed to lead to some local controversy, both at the time of publication and beyond. This was due to the impression given to the reader regarding the mode of speech, superstitions and attitudes of the three protagonists. The item is entitled ‘The Haunted Pit’, and the story centres on a long-missing miner from Guardian by the name of ‘Get-it-to-go’. Unexplained noises came from a nearby pit, and a figure of a man was occasionally seen passing by the local cottages. Finally a decision was taken – the pit must be examined in the hope of discovering the cause – and perhaps establishing Get-it-to-go’s fate - once and for all. Sure enough the exploring party found the man’s remains in the pit and it was removed for burial. The basic story is augmented by a conversation (set prior to the discovery of the body) between two colliers and their friend Nine Eyes, who plan to walk to the pit to investigate the noises. It is written entirely in Rev. Nicholls interpretation of the local Forest dialect. During a discussion as to the probable haunting of the mine, Nine Eyes comments, ‘.Who knows but what Get-it-to-Go’s ghost is a working of it round to let us know that he aint be sarved aright, and that it wants to be looked into’. This book, this particular story, and indeed the author, were not universally loved. Writing to the Hereford Times in September 1863, soon after the book was published, one Joseph James of Ruardean Hill states: 'He has published a work calculated to insult and alienate his parishioners. The superstitions which he states are in existence everywhere are decidedly a mistake....’ The letter writer concludes – in what at first glance it appears to be a positive statement, but from what has gone before would appear to be anything but: - ‘The affection he has for his people may be imagined from the way in which he treats them; and the love his people have for him may be estimated from the number who attend when he officiates’. As late as 1880, some 13 years after his death, doubts about the accuracy of certain material within this book were still being expressed in the press. Commenting on information in the volume about one such family (the Kembles, possibly linked to the Siddon family of Lydbrook) a letter writer states ‘the (works) are of no small interest, but their accuracy must not be relied upon farther than Mr Nicholl’s personal knowledge and observation extended’ (Stroud Journal, 8thMay 1880, page 2-3).

Iron Making in the Olden Times (1866)

This book contains a detailed extension of the chapter about iron mines and workings previously covered in his first publication. Nicholls refers to archival sources ‘extending back to the Middle Ages’, and following a brief outline of evidence of Roman finds in the area, he describes in great detail the furnaces of the Forest and the notable people involved in their operation at different points in time. He also includes such details as the levies placed by the Crown (who owned the land), on those that worked it. In addition to the verifiable facts there is interwoven some material that is perhaps more debatable in terms of accuracy / provability (a recent Reading the Forest podcast focussed on one such entry, regarding a plan by the Spanish, at the time of the Armada, to set light to the Forest of Dean – alluded to as ‘fact’ within the book). The book contains details taken from inventories of all forges in the Forest; including one undertaken by the Crown in 1635 (this inventory also is included as an appendix in his first book). It describes all the buildings and equipment on each site, and provides a glossary of words associated with the industry at the time. The 1635 inventory includes the following entry for Soudley (Sowdley) Forge: -‘2 Fineries, 1 Chaffery, built 2 years, in the place of the old Forge. Trows and Penstocks made new by the Farmers, decayed’.

While the following explanation is provided for the term ‘Moulding Ship’: ‘An iron tool fixed to a wooden handle: so formed as to make gutters in the sand for the casting of pig and sow iron’.

Perhaps surprisingly, given its date of publication, the book does not include details of more recent local developments in the iron industry - such as that being undertaken by the Mushets. Only brief reference is made to David Mushet, regarding an ancient piece of cast iron he had found which he believed to date around 1620.

This book contains a detailed extension of the chapter about iron mines and workings previously covered in his first publication. Nicholls refers to archival sources ‘extending back to the Middle Ages’, and following a brief outline of evidence of Roman finds in the area, he describes in great detail the furnaces of the Forest and the notable people involved in their operation at different points in time. He also includes such details as the levies placed by the Crown (who owned the land), on those that worked it. In addition to the verifiable facts there is interwoven some material that is perhaps more debatable in terms of accuracy / provability (a recent Reading the Forest podcast focussed on one such entry, regarding a plan by the Spanish, at the time of the Armada, to set light to the Forest of Dean – alluded to as ‘fact’ within the book). The book contains details taken from inventories of all forges in the Forest; including one undertaken by the Crown in 1635 (this inventory also is included as an appendix in his first book). It describes all the buildings and equipment on each site, and provides a glossary of words associated with the industry at the time. The 1635 inventory includes the following entry for Soudley (Sowdley) Forge: -‘2 Fineries, 1 Chaffery, built 2 years, in the place of the old Forge. Trows and Penstocks made new by the Farmers, decayed’.

While the following explanation is provided for the term ‘Moulding Ship’: ‘An iron tool fixed to a wooden handle: so formed as to make gutters in the sand for the casting of pig and sow iron’.

Perhaps surprisingly, given its date of publication, the book does not include details of more recent local developments in the iron industry - such as that being undertaken by the Mushets. Only brief reference is made to David Mushet, regarding an ancient piece of cast iron he had found which he believed to date around 1620.

For anyone having an interest in exploring the history of the Forest in depth, or undertaking family history research that might lead them to people mentioned by name, all three books were and remain a valuable resource, bringing together a vast array of original source material in one place.

later life & death

Sadly, Rev. Nicholls was forced to leave the Forest of Dean in early 1866 due to ill health. When the vacancy was formally advertised, just 4 days after his death, the post was described as being in the gift of the Crown, and to be worth £150 per annum (London Evening Standard, 4th January 1867, page3). Subsequent to his death in January 1867, the congregation of Holy Trinity Church elected to erect a monumental tablet, to be placed in the chancel of the church. The tablet, reports indicate, was to be ‘chased and beautifully executed’. His replacement at the church, Rev. William Barker, acted as treasurer for the fundraising (Monmouthshire Beacon, 20th April 1867, page 5). A later description of the tablet cited that it had been erected by his parishioners and friends, in recognition of his Christian character and fidelity as a Minister of Christ, and in recognition of his promotion of the building of schools and the formation of Parochial Friendly Societies. All these had endeared him to the memory of Foresters (Gloucester Journal, 28th November 1868, page 8).

Many thanks to Caroline Prosser-Lodge for her research and writing for this page.