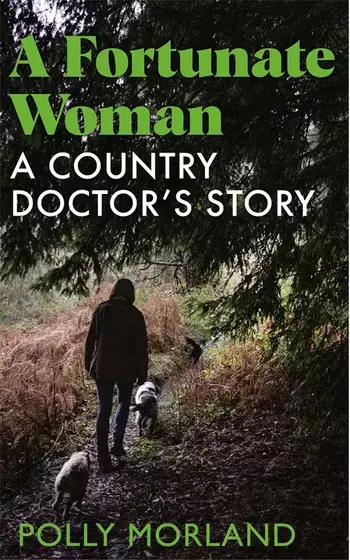

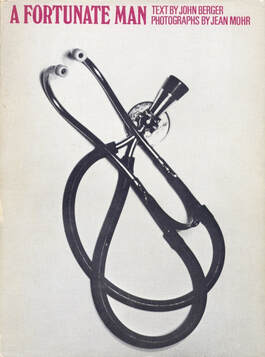

And it too is a remarkable, gripping and inspiring book that itself must surely become recommended reading for today’s trainee GPs.  Poly Morland is an award-winning documentary maker, journalist and author. She came upon Berger’s book by chance whilst clearing out her mother’s house in the summer of 2020. Picking up the dusty paperback copy that had fallen down the back of a cupboard decades ago, she instantly recognised one of the photographs: it showed the very same rural valley where she now lived. ‘Not only was this my home, my valley’ she writes, ‘but I too knew the doctor, his successor, the woman who serves this community today’. Unsurprisingly perhaps, when she contacted her, Morland’s doctor knew of Berger’s book, indeed it was part of the reason she too became a doctor: yes, they should meet. And so began their collaboration on this wonderful new book. A Fortunate Woman owes a great deal to its predecessor in regard to its approach and structure. It’s exact setting is never explicitly named, though of course, as the anonymity in the original was blown by a sensationalist tabloid newspaper piece, today a simple online search will divulge the identity of ‘the valley’ that Eskell and now Morland’s doctor serves. Where Eskell became ‘Sassall’, Morland’s doctor is never named – pseudonymously or otherwise. In both cases this gives their authors licence to exploit techniques more akin to the writing of novel in order to explore the inner lives of their subject. Based on close observation, interview, and in Morland’s case extracts from the personal journal of her doctor, yet not adhering in every detail to exact biography, the authors are free to combine and reconfigure incidents in order to better get at underlying truths. These are of course the stories of individual doctors, replete with biographical detail, yet they are not biographies as such. Rather, the part-anonymity of their protagonists allows these to be stories of doctors more generally; professionals in a role whose motivations and approaches to their work owe as much to more general institutional, social and geographical circumstances, as they do to individual personalities. Both books use anonymised patient consultations and histories as a means to explore the doctor-patient relationship in depth, as well as particular approaches to clinical practice. Alongside the personal histories of the doctors, it is these case histories that provide much of the narrative drive. They also, at points, provide moments of heart-stopping drama. Some of Morland’s descriptions of the GP’s inner thought processes and decision making when faced with rapidly emerging life and death situations are breath-taking. We see a doctor who perceives these situations in all their human dimensions and implications rather than merely as detached professional challenges. Berger and Mohr’s book is now 55 years old, and as GP Doctor Gavin Francis wrote in the introduction to the 2015 reissue of A Fortunate Man, it is now ‘a memorial not just to this exceptional individual but to a way of practising medicine that has almost disappeared.’ It is a book that is to be honest showing its age, not just in terms of the transformation of medical practice, but also in the wider social and literary context of its writing. Berger as author is a commanding presence in the book, untroubled by later academic theories that brought into question the authority of such an unequivocal authorial voice. Its author is almost as much protagonist in the book as ‘Sassall’ is in the life of his rural community. Reading A Fortunate Woman, Morland is also very much precent as author. Whilst her relationship to the doctor, Berger’s book, and the wider issues facing contemporary primary care are clear, they are also far more lightly held by the text, never interfering with the presence and story of the doctor and her patients. Berger’s intense focus on the doctor precluded, as he himself acknowledged, any significant mention of Eskell’s wife Betty who was not only a vital support to Eskell personally (Eskell suffered from depression) but also professionally in helping to run the practice. He was also supported in reality by a cast of pharmacists, district nurses and other professionals – not that you would know it from the book. Reading A Fortunate Man today it is to read a book of its time: the politics, the cultural assumptions, the social concerns expressed through the cases. Without wishing to over emphasise this, it is too, a book written about a male professional, by a male writer. They share a great deal in terms of social circumstances and outlook too, as well as cultural tastes. As Eskell’s late son pointed out, his father relished the many dinner party conversations on art, books and music with the likes of Berger and his friends. This was a period in which both medicine and literature were still dominated by the voices of men. In contrast, the experience of reading Morland’s book today is then one of being blasted by a gust of fresh, clear, contemporary air issuing from its writing and sensibility.

As in Berger’s book the patients are anonymised combinations and reconfigurations of real case histories, but in Morland’s their more familiar contemporary situations, problems and concerns, coupled with her considerable skill as a writer and communicator, make for more fully rounded, more real, more relatable and engaging figures. We read about gender transition, coercive control, Alzheimer's.

There are other changes in the make-up of today’s patients too. Morland’s doctor has far more elderly patients, with their attendant issues of dementia, decisions around care and the wider impact on partners and family, and end of life care too. She has twice as many patients now than Eskell did. Though much of her work is based at the surgery she still makes house calls, the former doctor’s Land Rover replaced now by an e-bike. Morland’s doctor is, all the same, as she describes her a kind of practice ‘grandchild’ to Eskell. Indeed, his former partner was still in place when she started there, and she worked alongside him until he retired. She shares Eskell’s whole-patient approach too, and treasures the unique value of such continuity of care that can only be achieved by a doctor who stays in a practice for years and is deeply embedded in her community. Yet, so much has changed. Morland describes the increasing pressures of a risk management approach to medicine: ‘…standardized guidelines trumps the judgement of individual doctors. Thus by increments the axis has tilted from an emphasis on the patient to an emphasis on disease, from interaction to transaction’. She acknowledges that her doctor’s approach is one that is in its turn at risk of disappearing with mounting pressures on all GPs time and resources. Berger came to know Eskell when he moved to a village near-by to Eskell's soon after marrying his second wife. Remembered by one elderly villager as coming into her parent’s shop to buy cigarettes, he otherwise doesn't seem to be remembered as mixing a great deal outside a small circle. By the time he decided to write about Eskell he’d long moved away, coming to stay for six weeks with the doctor in order to observe him at work. Berger’s descriptions of Eskell’s patient community have drawn much criticism for what some have considered to be glib and dismissive generalisations. To be fair, much of the weight in regard to portraying this community was, by design, intended to be borne by Mohr’s photographs. Even so, there is a sense that Berger just didn’t spend enough time getting to know the character of the people and places in which Eskell worked. In contrast, reading A Fortunate Woman is a far more enlightening experience. Morland, like her doctor protagonist, has an amazing ability to read, understand and describe people. And, like the doctor, living amongst, being embedded in this community, she has a depth and richness of understanding of it gained only through the continuity of living in one place for a length of time. This also enables Morland to describe the valley's landscape over time, and how it changes through the seasons: a practical consideration for a rural GP, but also something to be marvelled at and enjoyed as a salve to the soul on difficult days. In Morland’s hands this is a landscape and natural world that exists on its own terms too, not merely as an anthropocentric backdrop to human drama. Morland clearly has a love of and feel for nature, describing in detail its sights, sounds and smells during the course of the year. This subtlety of observation and description extends to her writing about the doctor too. There are detailed insights into her body language and tone of voice during consultations that seem to place you there in the surgery, witnessing the skill and warmth of this able and empathetic doctor. Reading Morland’s writing we get to know, feel, and appreciate the personality of this place, its people, and most importantly its thoroughly likeable and highly capable doctor. In the latter half of the book COVID arrives, providing a fascinating and gripping GP’s-eye view of the pandemic. Caught up in the practicalities of delivering diagnosis over the phone; deciding who needs admission to hospital with all the risks of infection that entails; and later, arrangements for delivery of vaccines; it is only once the doctor herself is vaccinated that, prompted by the palpable relief of her sons, she acknowledges the risks she has been exposed to during the pandemic. In practical terms, for Morland, the pandemic impacted on another aspect of the book: the photographs. With events and gatherings on hold during the creation of the book due to COVID restrictions, the opportunity to capture the vitality of communal life in the valley was impossible for photographer Richard Baker. What we have instead are images of the doctor decked in PPE, brooding landscape, and patients wearing masks. In this regard we have less to enjoy than in Mohr’s photographs, but Morland’s book is not any lesser for it. A Fortunate Woman is an important book – not least for its description of how we would want our doctors to be, to do their work, to relate to us, to make a meaningful impact on our health and wellness, something that is sadly at risk of disappearing. Whether or not it continues to be a reality, this book provides a valuable blueprint. It is too though a thoroughly enjoyable book to read, a series of fascinating and moving stories; centred upon an engaging and at times quite awe inspiring protagonist - this very particular doctor. A Fortunate Woman: A Country Doctor’s Story by Penny Morland, with photographs by Richard Baker, is published by Picador, price £16.99.

0 Comments

|

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed