|

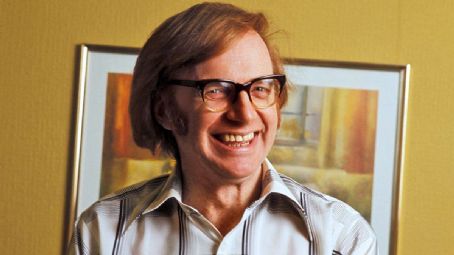

There was nothing out of the ordinary about a birth that took place on this day (17th May) 1935. The mother and father were living with her parents (not uncommon at the time), and so cramped were conditions that the birth took place at a neighbour’s house. The child was born at Brick House in Joyford on the edge of Berry Hill in the Forest of Dean. There was little that was remarkable either about the child as he grew up, playing in the woods, watching his grandfather in the village silver band and his mum and dad regularly doing a musical ‘turn’ at the local club. But he did well at school, and academic success for this son of a Forest coal miner would lead to a world of possibilities. After National Service he was off to New College Oxford where he plunged wholeheartedly into student life – taking part in drama productions and becoming editor of the prestigious student newspaper The Isis. The old pre-War class barriers were beginning to breakdown, and more opportunities were opening up. So, what would this young man do with his ‘shiny new degree’? We remember Dennis Potter today for his remarkable career in television, and perhaps here in the Forest of Dean most of all for his dramas Pennies from Heaven (1978), The Singing Detective (1986), and Cold Lazarus (1996) all featuring locally shot scenes (as well as local extras). There was the earlier – and for some, controversial – Wednesday Play A Beast with Two Backs (1968) much of which was also shot on location in the Forest. Television was Potter’s true passion and he had a huge impact on the development of television drama in particular. But his talents and interests were by no means limited to that one medium. He was a prolific journalist too (see The Art of Invective: selected non-fiction 1953-94, published in 2015), screenwriter for cinema, playwright for the stage, producer and director, cultural commentator, and even at one point stood for Parliament. And of particular interest for us at Reading the Forest, he was an author too. He wrote his first book, The Glittering Coffin (1960), whilst still at university. It was a ‘state of the nation’ work commenting on the society and politics of the time. It was highly personal in places with Potter writing in some detail (though briefly) about the Forest of Dean by way of example. At one point he admits, ‘I cannot hope to convey all that has happened in this district, but intend to produce a detailed study of the breakdown of a distinct regional identity at some future date’ (p44).  In 1962 his second book, The Changing Forest was published, and in some ways, it was indeed simply an expansion of those few paragraphs he’d written about the Forest in A Glittering Coffin. It was also though a more crafted and controlled expansion of the themes he’d touched on his BBC television documentary Between Two Rivers (1960). His first major piece of television work (he’d already appeared briefly in the documentary Does Class Matter whilst still a student and had worked on Panorama as a BBC trainee) that he wrote and presented, had upset many people in the Forest (though not all) who saw it. The opening half in particular saw Potter appearing to criticise his family and friends in the Forest, before later in the programme admitting he’d now changed his thinking and could now see the vitality and value of the Forest’s community and culture. In his book, The Changing Forest, Potter had the space, and the control over content, to express some of the detail and nuance that he wasn’t able to in the television format of Between Two Rivers. In the book (that shares a great deal with the programme) he spends more time with people and explores themes at greater length and in more detail. Potter as author is able to order and shape both evidence and argument in a way that he simply couldn’t in the television documentary. Potter’s developing skills as a journalist are clearly evident in The Changing Forest, but his authorship, just as in his work for television, would soon turn towards fiction-writing – art the better form, he realised, for telling truth. In all Potter would write four novels, and like his television dramas, they are often complex and challenging. As a young man he’d begun working on a novel, The Country Boy, though he never finished it. The various manuscripts of it are today housed in the Potter Archive at the Dean Heritage Centre (available to view on request). A few lines stand out as particularly poignant to those of us who know the Forest of Dean well. The young protagonist, David, is moved away from the Forest of Dean and is at a city-centre school in Fulham (just as Potter had). The other children refer to him as ‘the country boy’ because of his speech, but he finds it: ‘impossible to explain, he came from a hilly, green and lovely certainly, yet coalmining part of England, on the border of Wales. The Forest, the land on its own. Not just “the country”’ (for further details and analysis of this work see Carpenter, 1998, p86-88). There other scenes in the unfinished story that reappear nearly thirty years later in The Singing Detective, just as in a similar fashion the novels that he did complete and publish would inspire - or be inspired by - some of his other television work.  Potter’s first published novel was Hide and Seek (1973). Arguably a masterpiece of post-modern literature, the book plays to great effect with the novel form and the whole concept of the omnipotent author. Reading this challenging and exciting work it becomes clear that several of its ideas also made their way into The Singing Detective, (and later into Karaoke, 1996). The blurring of boundaries between author, protagonist and text, are particularly striking, as is one scene in particular, featuring a psychiatric consultation, all of which reappear in his television drama. Like much of Potter’s television work, the novel features seemingly biographical elements. It’s protagonist, Daniel Field, like Potter, went to Oxford, and he grew up in the Forest of Dean; the narrator in the book suffers from the same devastating skin disease as Potter; and Potter is known to at one point have had an appointment with a London psychiatrist. But as Potter would often explain, a writer’s experiences are merely the raw material he draws on and reshapes rather than a literal retelling of biographical incidents. As his biographer Humphrey Carpenter wrote, Potter’s message in this complex and tricky novel seems to be aimed at any future biographers: ‘I have been playing hide-and-seek with you. You think you are writing my life, but I am leaning over your shoulder, writing it for you. You, even you, are a character in my story. I can manipulate you too’ (Dennis Potter: The Authorized Biography, 1998, p291).  Potter's next novel, Pennies from Heaven (1981), was a far more straightforward work. After his 1978 BBC television serial, memorably featuring actors ‘lip synching’ to popular songs of the 1920s and 30s, and scenes filmed in the Forest of Dean, Potter had adapted the script for an MGM film released in 1981. Around the same time he turned the now USA-located narrative into a novel, the main challenge being that of conveying the same ideas without the musical elements of the film and television versions.  Ticket to Ride (1986) saw a return by Potter to previous form regarding his novel writing. Much like Hide and Seek, this novel was again dealing with themes of male sexual desire, breakdown, and the seemingly fractured self. The book opens as the protagonist suffers amnesia on a train as it arrives into Paddington Station, a moment of catastrophe that triggers a seeming division of John Buck, and the introduction of his internal ‘secret friend’. Potter is said to have written it in a burst of creative energy over 60 days, whilst also working on drafts of The Singing Detective screenplay (Carpenter, p446). The book was well received by the (literary) critics and was even considered as an entry for the Booker Prize (John Cook, Dennis Potter: A Life on Screen, 1995, p208). Again, there were elements in this novel that relate to some of his previous television plays. He went on to adapt it for the screen becoming the film Secret Friends (1991) starring Alan Bates and Gina Bellman, a film Potter himself directed.  He would go on to adapt his next novel Blackeyes (1987) also for the screen, this time as a four-part television drama of the same name broadcast on BBC2 in 1989. The TV adaptation starred Gina Bellman as a model and niece of an ageing writer (who in the television version also narrates her story). Potter dedicated the book to his daughters (Sarah and Jane, in their twenties at the time), and in it he addresses how advertising - culture more widely – commodifies and objectifies women’s bodies. He later explained how this was by extension a comment on broader culture and society. But what was perhaps safer territory to explore within a novel made for a far more problematic and controversial television outing, inducing criticism for what many saw as its own objectification of women. In the novel Potter again addresses the issue of ‘authorship’ through both the character of her uncle, himself a writer who seeks to exploit his niece’s experiences in his own work, and the ‘author’ of the novel we are reading, himself another character, ‘Jeff’, in the book (Cook, p261). Potter saw television as a means of communication that cut through the old class barriers that divided the audience of ‘high art’ (high-brow literature, fine art, opera etc.) from that of the ‘popular’ (pop music, variety entertainment, etc.). Television offered the opportunity to speak to all parts of society at the same time and Potter seized it. His feelings towards the novel as a form were more ambivalent. On the one hand he felt that writing a novel gave him ‘a certain freedom and relief’ from the demands of writing for the screen, whilst at the same time he believed that the novel as a contemporary form of writing ‘is almost dead’ (Potter On Potter, 1994, p127).

If the only work Dennis Potter had ever produced were his four novels he would surely demand our attention, and in the Forest of Dean some pride in his achievements. The fact that they represent the merest tiny fraction of his creative output is instead remarkable (see W. Stephen Gilbert's Fight & Kick & Bite: The Life and Work of Dennis Potter, 1995 for an excellent list of all of Potter's work). Yes, Potter will rightly be remembered and celebrated for his contribution to television. In the Forest of Dean in particular he will be remembered for the plays that saw the exciting world of television production set up shop (temporarily at least) in the neighbourhood. Of his books, if at all, it is his record and analysis of the area in the 1960s, The Changing Forest that continues to resonate to this day. But, whether in the Forest of Dean or anywhere else in the world, despite Potter’s own thoughts on the novel, pick up one his books for a change, and marvel at the genius of this sorely missed fine mind and creative talent!

0 Comments

Local history researcher Steven Carter recently came across a fascinating publication from the early nineteenth century. A Brief and Authentic Statement (1818) by the Reverend Payler Matthew Procter offers some fascinating insights into the Forest of Dean at the time, and for Steven in particular has resonated with his own own family history.

Now a retired teacher, Steven attended Lydney Grammar School in 1970s. Steven says, ‘My father is a true-born Forester, like his father, who was a life-saving hero of the 1949 Waterloo Colliery flooding. My Grandmother Cooper’s fascinating family history goes back hundreds of years at Berry Hill. Exploring the context for these roots and especially interviewing former Waterloo Colliery workers has made me a local history enthusiast. The Forest has a most fascinating history.’ Steven recently put on exhibitions about the Waterloo Colliery flooding at Hopewell Colliery and the Dean Heritage Centre. He has also written articles about the Colliery, the Mitcheldean industrialist and philanthropist Timothy Bennett (1804-61), and the 1861 Speech House Murder. He continues to be interested in anything connected to Waterloo Colliery. At the moment he is also investigating the history of the song 'The Jovial Foresters' and, how Edward Protheroe used slavery wealth to develop Forest tramroads, ironworks and collieries. REV. PROCTER'S BRIEF AND AUTHENTIC STATEMENT (1818) In The Changing Forest (1962), Dennis Potter laments pit closures and the ‘decline of the distinctive Forest culture’ of his childhood. He attributes the erosion of traditional ways to the onslaught of mass media and consumerism’s ‘newer, brighter, corroding uniformity’ (p10, 132) Reverend Procter’s Brief and Authentic Statement (1818) reveals a social and cultural revolution in the opening decades of the nineteenth century, comparable to and perhaps more fundamental than Potter’s. Procter narrates how the Anglican Church and an associated school became established at Berry Hill, and in doing so he incidentally provides glimpses of an older, more original Forest culture. Procter’s memoir swings through many forms, from simple narration, to sermon, theological tract and proof texts, to ecclesiastical and even salvation history; all helpful for understanding his Anglican perspective. For me, however, with my Grandmother’s Cooper ancestors among those earliest Berry Hill folk, of particular interest are those glimpses of the Forest community before the Church held sway. This old Forest culture was about to undergo profound change, as the outside influences of Church, Crown and Capitalists penetrated the Dean and transformed its inhabitants’ lives. Where some talk of ‘improvements’, others might say ‘dispossession’. As Chris Fisher showed in Market Capitalism: The Forest of Dean Colliers 1788-1888 (1981), market capitalism replaced customary rights and most independent miners became wage labourers. With Procter we catch the beginnings of this process, with important insights into the ‘Before’. Background Saxon and Norman kings had preserved the Forest as a royal hunting ground, but in later centuries the Crown became more interested in exploiting its resources, especially the iron, coal, stone and timber. Freeminers in small-scale operations, other Forest workers and local entrepreneurs, and the destitute and marginalised, settled inside the boundary whenever the authorities were weak. Each time the Crown regained strength, their crude cabins would be dismantled and squatters removed. In the late eighteenth century, however, the Deputy Surveyor responsible for the Forest reported that he had to desist from pulling down cottages, fences and inclosures because the encroachers’ repeated insults and threats made him fear for his life and property. By 1788 over 2,000 cottagers were established in 1,398 acres, with 589 makeshift cabins, many looking ‘too miserable for human occupation’, but others of stone or brick-built (By the 1830s the houses grew to 1462, with 2108 acres, until the Dean Forest [Encroachments] Act of 1838 allowed the older encroachments and prohibited further ones. In Warren James and the Forest of Dean Riots (1986) (p8-11) Forest author and historian Ralph Antis described this world, between the Severn and the Wye, cut off from mainstream English social and economic life: "the geographical isolation of the foresters… was compounded by [their work]. Miners everywhere form closed communities, but… their isolation was increased by their absolute refusal to allow anyone from outside the Hundred of St Briavels to join [their mining…] They call such outsiders ‘foreigners’". This wild country’s dark and frightening paths and threatening inhabitants deterred strangers. Writers before 1820, educated and well-to-do outsiders, agreed about the Foresters’ ‘wildness and lawlessness’; and showed little sympathy for their hard lives. Nevertheless, the Mine Law Court documents suggest a community centred around responsible freeminers, with a very sober, intelligent and orderly approach to solving their problems. Anstis concludes that the Foresters could be tough, touchy and fiercely independent - such that governments tended to leave them alone -, until the Crown’s increasing economic development and efficient management of the Dean confronted the Foresters with a challenge that would produce the biggest change in their way of life that they had ever known, provoking the Warren James riots and further government attempts to rationalise and control the Forest. Eventually, in the 1830s, the Dean Forest Commission and ensuing legislation imposed a new settlement on the Forest. The continued presence of sheep roaming the Forest and Freeminers underground, however, are modern day reminders that the Foreigners’ victory was not total. The Berry Hill Mission In 1803 Rev. Procter became Vicar of Newland. His interaction with the extra-Parochial Foresters was at first limited to visiting the sick and baptising babies. When Procter was to preach at Coleford Chapel, curiosity attracted some of the colliers and reports from these brought Freeminer Thomas Morgan. After hearing Procter’s preaching, Thomas became agitated in his soul and asked Rev. Procter to visit his home (next to the Church’s future location, that became the vicarage), where in deep conversation they discussed the fate of his soul. Thomas requested the Reverend to return next week, and if some friends and relatives could join them. Next Thursday Rev. Procter was surprised to discover a house so packed that he could hardly open the door to get in. Rev. Procter kept up these Thursday evening lectures for the coming years and his audience were unfailingly attentive. With benevolent intentions, a warm sympathy and prolonged effort, the good Reverend worked to prepare ‘these scattered people… for the Lord’ (p11). 'The Forest being extraparochial, it should be understood that the inhabitants have no right or power to command the services of any clergyman. A cold determination to do what is generally termed a benevolent act first induced me to go there. I saw nothing of them on the sabbath-day. The church was only used by them as a matter of course and necessity: indeed a general opinion prevailed that they had no right to accommodation, and a forester was seldom seen in the aisle' Procter admits also to a motive from ecclesiastical politics; to capture the Foresters before any Dissenter mission could. We can see that not everyone at Berry Hill welcomed these visits. This new way of life split the village. We can appreciate the sadness for Thomas’s friend who called on him to remember their good times together and re-join his former ways, but Thomas said their only togetherness could be for his former friend to stand where Thomas stood. Local curate and Forest historian the Reverend Nicholls' later comments (The Personalities of the Forest of Dean, 1863, p165) reveal the strong feelings aroused: 'These journeys into the Forest were not altogether free from danger. The old party did not like their sports to be interrupted. Until all fear from violence from them ceased, some portion of the congregation used to attend Mr Procter over the bounds of the Forest, after his Evening Lecture'. In this ‘culture war’ that split the village, ‘the old party’ might feel there was more at stake than interrupted sports. A new division was created and the community’s old ways were not surrendered without resistance. Thomas had the vision for a church and a school at Berry Hill and from his own generosity and effort, local contributions and two public appeals, these were established. Later legislation after the Dean Forest Commission incorporated the Forest into the Anglican parish system. Procter wrote his Memoir to help cover a debt of £950 that he had incurred by a technical fault when transferring property to set up the Church. His friends suggested the profits from this pamphlet could help pay off that heavy debt. Generations of my Grandmother Cooper’s ancestors attended the Church and many are buried in the graveyard behind. My special interest in Procter’s Brief and Authentic Statement, however, is not with any triumph of the Gospel, though it influenced generations of my ancestors’ worship and education. My Grandmother inherited a strong commitment to keeping Sunday special, and my Dad and his siblings attended the school and played on the triangle of grass outside. Since my own ancestors were among these early settlers at such evocative locations as Shortstanding, Joyford, Berry Hill and Hillersland, before ‘Christchurch’ was conceived, I have a special interest in the occasional glimpse Procter provides of their early Forest culture. Despite his churchman’s view of the Foresters, the much-loved Reverend provides direct views of his parishioners, including insights into their lives and Forest culture before the Established Church became an influential force in their community. The Older Forest Culture Although Procter criticises some Forest ways, his remarks also provide occasional perceptive insights into their culture. Procter’s account describes several aspects of Forest culture and life around Berry Hill from 1804 and earlier. ‘They are a people of themselves, of peculiar habits, tenacious in their dispositions, and from an idea, unfortunately too just, that the neighbouring parishes look upon them in an inferior point of view’ (p28). Based on ‘visiting of the sick’ and ‘baptizing of the children’, Rev Procter’s first impression – despite his feelings of sympathy and Christian love -‘was of the most unfavourable kind’, as he gained ‘knowledge of their condition, their lives and conversation, of which the latter were the most deplorable.’

'But what are the real evidences of a low, debased state of morals! is an habitual profanation of the Sabbath-day? are drunkenness, rioting, immodest dancing, revellings, fightings? are the want and ignorance of the holy scriptures? and is an improper state of females on their marriage? if these are allowed to be evidences of immorality, I have only here to affirm that they are facts, not opinions hazarded, but observations made; they are rending and harrowing truths. The general state of the women, in an especial manner, gave a convincing proof of a deep-rooted depravity, abhorrent to what the world calls virtue: how disgraceful then to the christian name and profession!' (p2-4) Procter’s words, remember, reflect his class and faith. We might look beyond the standards, to be imposed by his Anglican regime and consider the Forest community in their own terms, in the context of the hard lives they lived. Procter’s brief words on the daily dangers colliers faced evoked the precariousness of life for mining people. Considering my own ancestors were among these miners, this sentence struck me as chilling: 'Not a thought was permitted to intrude of the possibility that the pitin which he worked, might close its mouth uponhim, and his soul be required.' (p43) This reminded me of comments from former miners, like Eric Morris, Charlie Penn, Paul Morgan and Gordon Brooks. Each said they did not dwell on the dangers of work underground – even though all had recounted to me dangerous, life-threatening moments! Such matter-of-fact fortitude implicit in all mining helps explains why the Forest so respects and celebrates its mining heritage. Procter’s note, a minor detail, that colliers returned home from their pit at 7pm (p6), recalled vividly for me warm summer evenings in the Forest. Rev. Procter’s tireless exertions to fix the gospel in this extra-parochial part of the Forest and to minister to the Foresters resulted in building at Christchurch the Forest’s first parish church. Despite his benevolence, Procter also reflected the nineteenth-century preoccupation with sabbath-breaking – effectively controlling every minute of the lives of the lower orders, lest they revolt or fall into vicious iniquity! Importantly, he provides a marvellous window on a Foresters’ ‘scene of iniquity’ at Berry Hill, which today might be viewed more favourably. Thomas Morgan enthusiastically organised cricket matches, but on the Sunday Sabbath-day! ‘There was no fear of God before his eyes. Cricket matches were their favourite game, and hundreds assembled on the Sabbath-day to see the play. Old and young blended together, children and infants were brought, because their fathers and mothers could not come without them. Such was their mode of education, such was their Sabbath-day as handed down from father to son from generation to generation… Thomas [looked after]…the bats, balls and wickets… He was first upon the ground, and the last to quit… Thomas cast many a watchful, anxious look on [the sun’s] departing beams, and his heart throughout the sacred day first sighed when the evening shades compelled to desist from profaning that Sabbath which the Lord God blessed, hallowed, and commanded to be kept holy. On depositing in a place of safety the bats and balls, he looked forward to the next Sunday, regretting only the intervening six days.’ Today’s judgement might look beyond the sabbath-breaking and see a wonderfully inclusive community event, where the feared and rejected Foresters came together in a well-deserved break from their long days of hard labour in the dark depths of the earth. I am reminded, too, of Eric Morris’s almost poetic comment about how working in the dark pit helps miners appreciate even more the colours of the Forest: 'When we came up in the bond we used to look across at the trees by Lydbrook Vicarage. How green those trees were to us, never were trees so green. In the pit there were no colours, just black, or shades of black, only men’s eyes showed white. When you came up from the pit at the end of a shift it was wonderful to see colours. The autumn colours of the trees - that was almost like a reward for working down in the black. As we reached the surface that first glimpse! Only miners could appreciate to the full the green of the trees, the colours of autumn. Had anyone else walked with us from the pit they'd not have seen what we saw. They wouldn't have seen the blue sky, the green trees that we saw with our eyes'. (Eric Morris in Forest Voices: Recollections of Local People, 2008 by Humphrey Phelps, p91-92) Eric’s comments perhaps encourage our sympathy today with Thomas Morgan’s enjoyment of his Sunday cricket. We see in Thomas Morgan’s final days a fate that must have been replicated in many cottages (even up into recent times, as was the case for both my miner grandfathers, where pit work undermined their health). 'He had long been declining in health, and now becoming seriously ill, he gradually sunk down under a painful, tedious asthmatic affection brought on by the damps of the pits'. (p54) Thomas was not alarmed by ‘the awful prospectof death’, but was ‘sure and steadfast’ in his hope. 'He gave a faithful evidence of his unceasing love to the cause of God, by appointing his executors to sell his little property, either to myself or the trustees, on a fair valuation, if required for the school or the church. This intention however was providentially completed by himself before his death; as much to the satisfaction of his family as could be expected'. (p54) The reference to his family’s feelings on the matter perhaps leaves much unsaid! I wonder what their full feelings might have been. A final insight into the Foresters involves Thomas Morgan’s wish to be buried in the chapel he did so much to help establish. The visiting Bishop, much impressed by Thomas’s character and faith, could not grant his wish. Rev Procter considered the matter closed. But the last word on Thomas comes from his fellow Foresters. Sadly, Thomas Morgan died in the year 1816 when Christchurch was consecrated. It had no churchyard so he was buried in Newland Cemetery. Later twenty foresters armed with pick axes and shovels dug him up and reburied him where the South Aisle of the church is today in front of the pulpit, half way towards the door. The grave remains under the floor and a plaque is commemorated to all his hard work and vision. His name was the first to be recorded in the burial register when the ground was consecrated for burial (Christchurch Guide). This action was both a fitting final act in Thomas Morgan’s story and offers yet another insight into the Foresters of his day. In Conclusion... Procter’s Brief and Authentic Statement narrates the success of his Berry Hill mission. Hidden inside the text are priceless gems offering insights into the Forester community at the time, in the days before their world was transformed by Church, Crown and Capitalists! Take a look for yourself - you can read it online for free at Google Books, here. Steven Carter, 2021 For many of the Forest of Dean’s authors and poets writing was something that, by necessity, they fitted around - or at the end of - their working lives. This was doubly so for some of the Forest’s female writers who, as well as working, also ran the family home: Writing was something to squeeze in at the end of a busy day, or later in life once the children had left home. In the twentieth century the domestic and working lives of Forest women began to (slowly) improve, as we can see reflected in the writing and working lives of three female Forest authors.

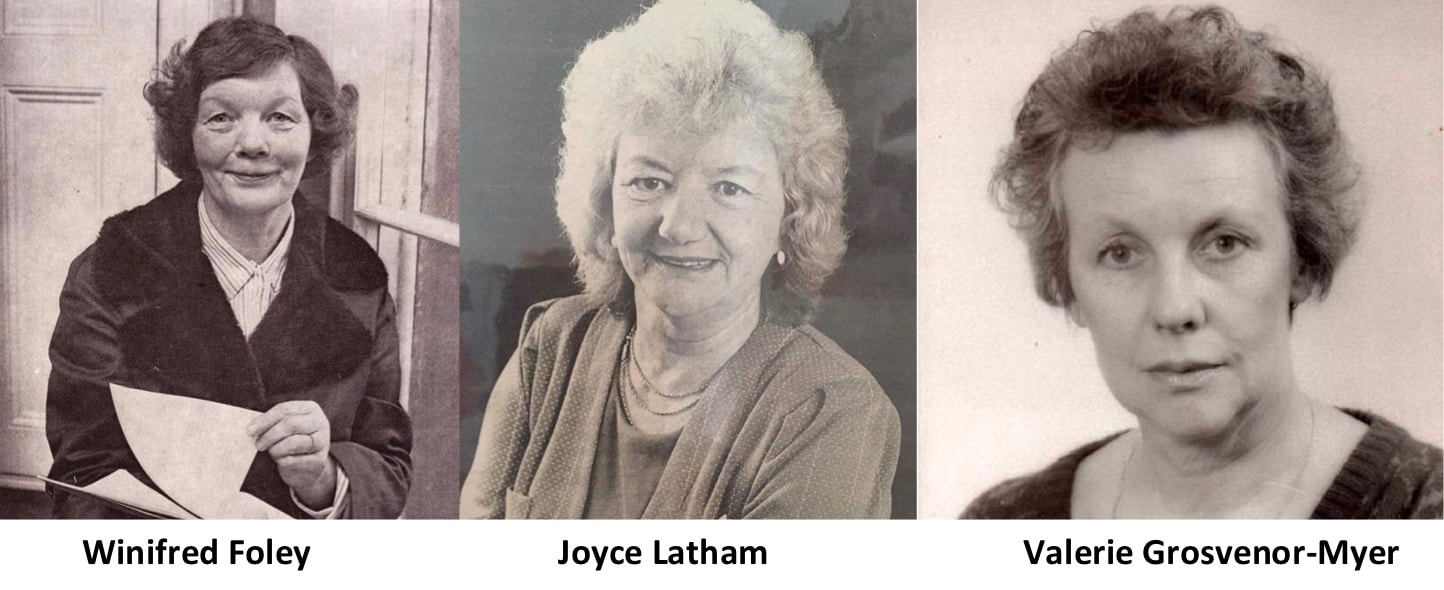

For Winifred Foley, born into a working-class family in 1914, there were few options but to join the army of Forest women and girls who worked in ‘domestic service’. This was something Foley wrote about so brilliantly in her debut book A Child in the Forest (1974). By the time Joyce Latham, born in 1935, joined the world of work other opportunities had begun to open up. In her memoirs - Where I Belong(1993) and Whistling in the Dark (1994) - Joyce writes about jobs in local shops, and in factories. By the latter half of the century entry by women into traditionally male dominated careers - such as newspaper journalism - were a possibility. Valerie Godwin (later to become Valerie Grosvenor-Myer), also born in 1935, started her career in journalism by writing for the Dean Forest Mercury. She would go on to write for national newspapers and become a respected literary editor, critic, academic and author of several significant literary biographies. Valerie’s time working at the Mercury is just one of the many splendid recollections in the latest episode of the Voices from the Forest podcast series. Episode 4 focuses on the transformations in the working lives of women in the Forest of Dean during the latter half of the twentieth century. Several of the interviewees talk about their jobs in domestic service before World War Two, often starting as teenagers in jobs many miles from their family and friends. But during and after the War there was better access to education and improved opportunities as the Forest economy shifted from the older heavy industries to an increasing reliance on lighter, high value manufacturing and factory work. The podcast offers a fantastic insight into the working lives of Forest women and provides brilliant historical context in which to understand the work of some of the female Forest authors of the twentieth century. You can find the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts and Anchor, or simply go the Voices in the Forest website’s Podcast page here (and click ‘play’ to listen). |

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed