|

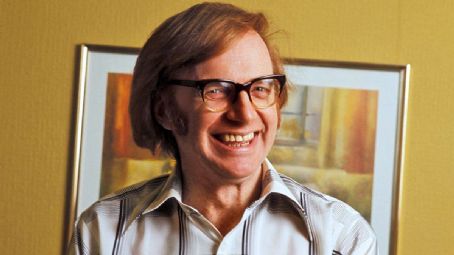

There was nothing out of the ordinary about a birth that took place on this day (17th May) 1935. The mother and father were living with her parents (not uncommon at the time), and so cramped were conditions that the birth took place at a neighbour’s house. The child was born at Brick House in Joyford on the edge of Berry Hill in the Forest of Dean. There was little that was remarkable either about the child as he grew up, playing in the woods, watching his grandfather in the village silver band and his mum and dad regularly doing a musical ‘turn’ at the local club. But he did well at school, and academic success for this son of a Forest coal miner would lead to a world of possibilities. After National Service he was off to New College Oxford where he plunged wholeheartedly into student life – taking part in drama productions and becoming editor of the prestigious student newspaper The Isis. The old pre-War class barriers were beginning to breakdown, and more opportunities were opening up. So, what would this young man do with his ‘shiny new degree’? We remember Dennis Potter today for his remarkable career in television, and perhaps here in the Forest of Dean most of all for his dramas Pennies from Heaven (1978), The Singing Detective (1986), and Cold Lazarus (1996) all featuring locally shot scenes (as well as local extras). There was the earlier – and for some, controversial – Wednesday Play A Beast with Two Backs (1968) much of which was also shot on location in the Forest. Television was Potter’s true passion and he had a huge impact on the development of television drama in particular. But his talents and interests were by no means limited to that one medium. He was a prolific journalist too (see The Art of Invective: selected non-fiction 1953-94, published in 2015), screenwriter for cinema, playwright for the stage, producer and director, cultural commentator, and even at one point stood for Parliament. And of particular interest for us at Reading the Forest, he was an author too. He wrote his first book, The Glittering Coffin (1960), whilst still at university. It was a ‘state of the nation’ work commenting on the society and politics of the time. It was highly personal in places with Potter writing in some detail (though briefly) about the Forest of Dean by way of example. At one point he admits, ‘I cannot hope to convey all that has happened in this district, but intend to produce a detailed study of the breakdown of a distinct regional identity at some future date’ (p44).  In 1962 his second book, The Changing Forest was published, and in some ways, it was indeed simply an expansion of those few paragraphs he’d written about the Forest in A Glittering Coffin. It was also though a more crafted and controlled expansion of the themes he’d touched on his BBC television documentary Between Two Rivers (1960). His first major piece of television work (he’d already appeared briefly in the documentary Does Class Matter whilst still a student and had worked on Panorama as a BBC trainee) that he wrote and presented, had upset many people in the Forest (though not all) who saw it. The opening half in particular saw Potter appearing to criticise his family and friends in the Forest, before later in the programme admitting he’d now changed his thinking and could now see the vitality and value of the Forest’s community and culture. In his book, The Changing Forest, Potter had the space, and the control over content, to express some of the detail and nuance that he wasn’t able to in the television format of Between Two Rivers. In the book (that shares a great deal with the programme) he spends more time with people and explores themes at greater length and in more detail. Potter as author is able to order and shape both evidence and argument in a way that he simply couldn’t in the television documentary. Potter’s developing skills as a journalist are clearly evident in The Changing Forest, but his authorship, just as in his work for television, would soon turn towards fiction-writing – art the better form, he realised, for telling truth. In all Potter would write four novels, and like his television dramas, they are often complex and challenging. As a young man he’d begun working on a novel, The Country Boy, though he never finished it. The various manuscripts of it are today housed in the Potter Archive at the Dean Heritage Centre (available to view on request). A few lines stand out as particularly poignant to those of us who know the Forest of Dean well. The young protagonist, David, is moved away from the Forest of Dean and is at a city-centre school in Fulham (just as Potter had). The other children refer to him as ‘the country boy’ because of his speech, but he finds it: ‘impossible to explain, he came from a hilly, green and lovely certainly, yet coalmining part of England, on the border of Wales. The Forest, the land on its own. Not just “the country”’ (for further details and analysis of this work see Carpenter, 1998, p86-88). There other scenes in the unfinished story that reappear nearly thirty years later in The Singing Detective, just as in a similar fashion the novels that he did complete and publish would inspire - or be inspired by - some of his other television work.  Potter’s first published novel was Hide and Seek (1973). Arguably a masterpiece of post-modern literature, the book plays to great effect with the novel form and the whole concept of the omnipotent author. Reading this challenging and exciting work it becomes clear that several of its ideas also made their way into The Singing Detective, (and later into Karaoke, 1996). The blurring of boundaries between author, protagonist and text, are particularly striking, as is one scene in particular, featuring a psychiatric consultation, all of which reappear in his television drama. Like much of Potter’s television work, the novel features seemingly biographical elements. It’s protagonist, Daniel Field, like Potter, went to Oxford, and he grew up in the Forest of Dean; the narrator in the book suffers from the same devastating skin disease as Potter; and Potter is known to at one point have had an appointment with a London psychiatrist. But as Potter would often explain, a writer’s experiences are merely the raw material he draws on and reshapes rather than a literal retelling of biographical incidents. As his biographer Humphrey Carpenter wrote, Potter’s message in this complex and tricky novel seems to be aimed at any future biographers: ‘I have been playing hide-and-seek with you. You think you are writing my life, but I am leaning over your shoulder, writing it for you. You, even you, are a character in my story. I can manipulate you too’ (Dennis Potter: The Authorized Biography, 1998, p291).  Potter's next novel, Pennies from Heaven (1981), was a far more straightforward work. After his 1978 BBC television serial, memorably featuring actors ‘lip synching’ to popular songs of the 1920s and 30s, and scenes filmed in the Forest of Dean, Potter had adapted the script for an MGM film released in 1981. Around the same time he turned the now USA-located narrative into a novel, the main challenge being that of conveying the same ideas without the musical elements of the film and television versions.  Ticket to Ride (1986) saw a return by Potter to previous form regarding his novel writing. Much like Hide and Seek, this novel was again dealing with themes of male sexual desire, breakdown, and the seemingly fractured self. The book opens as the protagonist suffers amnesia on a train as it arrives into Paddington Station, a moment of catastrophe that triggers a seeming division of John Buck, and the introduction of his internal ‘secret friend’. Potter is said to have written it in a burst of creative energy over 60 days, whilst also working on drafts of The Singing Detective screenplay (Carpenter, p446). The book was well received by the (literary) critics and was even considered as an entry for the Booker Prize (John Cook, Dennis Potter: A Life on Screen, 1995, p208). Again, there were elements in this novel that relate to some of his previous television plays. He went on to adapt it for the screen becoming the film Secret Friends (1991) starring Alan Bates and Gina Bellman, a film Potter himself directed.  He would go on to adapt his next novel Blackeyes (1987) also for the screen, this time as a four-part television drama of the same name broadcast on BBC2 in 1989. The TV adaptation starred Gina Bellman as a model and niece of an ageing writer (who in the television version also narrates her story). Potter dedicated the book to his daughters (Sarah and Jane, in their twenties at the time), and in it he addresses how advertising - culture more widely – commodifies and objectifies women’s bodies. He later explained how this was by extension a comment on broader culture and society. But what was perhaps safer territory to explore within a novel made for a far more problematic and controversial television outing, inducing criticism for what many saw as its own objectification of women. In the novel Potter again addresses the issue of ‘authorship’ through both the character of her uncle, himself a writer who seeks to exploit his niece’s experiences in his own work, and the ‘author’ of the novel we are reading, himself another character, ‘Jeff’, in the book (Cook, p261). Potter saw television as a means of communication that cut through the old class barriers that divided the audience of ‘high art’ (high-brow literature, fine art, opera etc.) from that of the ‘popular’ (pop music, variety entertainment, etc.). Television offered the opportunity to speak to all parts of society at the same time and Potter seized it. His feelings towards the novel as a form were more ambivalent. On the one hand he felt that writing a novel gave him ‘a certain freedom and relief’ from the demands of writing for the screen, whilst at the same time he believed that the novel as a contemporary form of writing ‘is almost dead’ (Potter On Potter, 1994, p127).

If the only work Dennis Potter had ever produced were his four novels he would surely demand our attention, and in the Forest of Dean some pride in his achievements. The fact that they represent the merest tiny fraction of his creative output is instead remarkable (see W. Stephen Gilbert's Fight & Kick & Bite: The Life and Work of Dennis Potter, 1995 for an excellent list of all of Potter's work). Yes, Potter will rightly be remembered and celebrated for his contribution to television. In the Forest of Dean in particular he will be remembered for the plays that saw the exciting world of television production set up shop (temporarily at least) in the neighbourhood. Of his books, if at all, it is his record and analysis of the area in the 1960s, The Changing Forest that continues to resonate to this day. But, whether in the Forest of Dean or anywhere else in the world, despite Potter’s own thoughts on the novel, pick up one his books for a change, and marvel at the genius of this sorely missed fine mind and creative talent!

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed