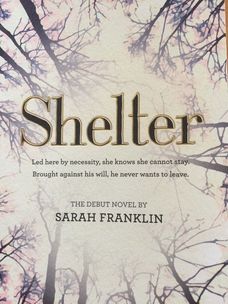

"The world was alive out here, the scent of bud and blossom in every breath a stark contrast to the thus of bombs into sandbanks, or worse, the iron smell of blood and the screams when a shell hit a target. This was a place where you could start again." The Forest of Dean and its familiar woodland is central to Sarah Franklin’s debut novel, Shelter. The Second World War provides the context for this lovely, well written story of the coming together of an Italian prisoner of war and a ‘Lumbergill’ seeking refuge from the Coventry blitz. These characters are, in their different ways both refugees, and like so many before they are taken into the bosom of a Forest family. They become part of the collective effort to fell the great oaks and woods of the Dean to support the war effort. Sarah Franklin, with an insight born of her own Forest heritage, captures the sanctuary that the woods offered and the mixture of emotions generated when swathes of great oaks were felled. The understanding of Foresters’ ways, their sheep, mines and dialect and the geography of the Forest are perfectly captured in this well researched book. For anyone familiar with the Forest the landmarks are well known; Parkend Memorial Hall and the Forestry Training School feature as part of the books landscape. The war time resilience, stoicism and compassion of the family at the heart of the book rings true. Their portrayal undermines the false representation of Foresters as traditionally being antagonistic to ‘vurriners’. Foresters may have been wary of exploitative capitalists but they were always willing to give ‘shelter’, as the name of the book implies, to those seeking refuge and the dispossessed. Connie, the central character, represents someone traumatised by the war. She is given the opportunity to make a new start and occupy a role that had traditionally been the prerogative of men. The training and experience of women employed in Forestry described in the book has a factual basis, researched by the author at Dean Heritage Centre. The unmarried Connie bears a child, an event that her surrogate family embrace - with less condemnation than was probable in the 1940s - but the author gives the Forest family a generosity that makes this believable. The ‘old Foresters’ in the book ring true and Amos, a sheep badger who supresses his emotions and appears to have a higher regard for his sheep and dog than people, is superbly realised and familiar. This is not a simple love story; Connie is restless and struggles with the comfort of her refuge in the Forest and has an ambition to ‘live the dream’, so the reader is never quite sure of a happy ending. The Italian participation in this story is built around the PoW camp at Wynols Hill. The legacy of the Italian presence in the Forest has been arguably more lasting than that of the American occupation. The wartime experience helped forged a bond that saw many Italians remain or return after the war and make names such as ‘Marangon’ as familiar as Smith or Virgo. This well written debut novel may draw the reader less familiar with the Forest to visit or investigate the impact of the war on the area. Sadly, the one memorable physical legacy of the camp – the Marconi monument – was a victim of Council short-sightedness and demolished in the 1970’s. The trees have thankfully recovered from the ravages of war. However, Forest heritage is built on stories not monuments, and this story of love, identity and finding happiness will appeal to a local audience and contribute to our idea of ourselves and our past. Shelter by Sarah Franklin, published by Zaffre, available from 27 July, 2017.

1 Comment

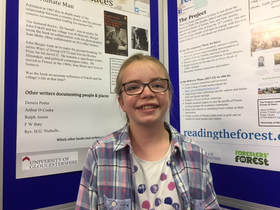

Sunday (9th July) saw the culmination of this year's fantastic Coleford Festival of Words. After a week of readings, talks, and performance in Coleford, the festival decamped for its final day to Hopewell Colliery Museum for a celebration marking 800yrs of the Forest Charter. The day included a historical 'street' theatre performance lead by festival instigator Roger Drury telling the story of the Forest of Dean from Roman times to the prsent day. There was music, exhibition, stands, and art as well as tours underground. Speeches came from people involved in the HOOF and FOOF campaigns, including one Peer, and one of Her Majesty's Verderers! The event was opened by no less than the one Lord Lieutenant. A stand out moment was the performance of Vorest Miner by Hawks class of Lydbrook Primary School. Reading the Forest were very pleased to be asked to take part in the festival - as well as simply enjoying the many of the events! Amongst many highlights of the previous week, the fantastic Hollie McNish performing to a full house at Coleford Baptist Church stood out. Another has to be the first Forest performance by the fabulous Project Adorno of their mixed media live show Dennis Potter in the Present Tense. And the festival was not just established writers - it included a writing competition to spot new talent. Winner of the Reading the Forest sponsored youth category was 13 yr old Izzy for this fabulous piece in response to call for entires on the theme of 'reading'. Read Izzy's entry here: 'Him'

A browned envelope lay on the table. Part of me knew what it was, so I don’t really know why I looked. But part of me was longing, optimistically hopeful that I was mistaken in its purpose. I sat down in front of it, and neatly sliced it open with my letter opener. It just seemed the most respectful thing to do. Two other parts were now peeking out, crumpled at the edges but still formal. Gently, I pulled on the corners. Out flew a letter, neatly addressed to Mother and I; the remaining, a picture of him. Out that came too, and rested silently on the table. It was certain. No more pretending, hoping. An ocean-full of tears swam in my eyes, but only one fell; one in a hundred; him. I didn’t read all of the letter. There was no point. I could see the first paragraph or so from its folded position on the table, enough to know. I pushed it to one side, unable to bear to look at it any longer, its black, heartless writing, and neatly pressed edges. Instead, I looked at the picture - a brilliant photograph of him and his steed. A beautiful chestnut mare - I knew from his letters. A worthy horse for him. His face was cheerful, his uniform smart and new. It was like he knew, but, like me, didn’t want to. Around him, other men were busying themselves with chores - cleaning stables, brushing horses and polishing guns - their moustached faces contrasting perfectly with his clean-shaven one. His face, round, smiling, loving. I walked unsteadily to my room, the little box room on the side of his. Carefully I placed his photograph on top of a shelf beside my bed. Next, I tore off a sheet of my precious writing paper - it was worth it for him - I proceeded to, in my neatest writing, write seven words and fold the paper to stand next to his picture. His last words to me before he’d gone - ‘stay strong, and hope will find you’. Then I unceremoniously collapsed onto my bed and wept. The reality had reached me. My father. Dead. He seemed to watch me from his perch, and comfort me. He would always be there for me. My father. In heaven, guarding me. |

Archives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed