James g. wood

EARLY LIFE

James George Wood was born in December 1843 in New South Wales, Australia, and was baptised the following July at Wollongong St Michael Church, New South Wales. He had one older brother, Edmund Gough de Salis Wood (1841 – 1932). Soon afterwards the family returned to the UK and James would have spent the majority of his childhood living in Tutshill, close to both the border town of Chepstow and to the Forest of Dean.

James' father, Edmund Fowle Wood, was born in Sandwich, Kent in 1808, the eighth son of timber merchant James Wood, and his wife Susanna. As a young man Edmund worked for the East India Company. At the time of Wood’s baptism in 1844 Edmund is described as a gentleman settler in New South Wales. Family records indicate that he ran a dairy farm. After some five years in the colony the family returned to the UK. They lived for a short time in Llansamlet, Ystradgynlais, Glamorgan, with Edmund then working as a railway contractor. Ultimately, however, the family settled in Elm Villa, Tutshill. Railway records show that Edmund continued to be employed in the Chepstow Estate Office of the Great Western Railway company until 1877 (UK Railway Employment Records, 1833-1856). He additionally acted as a land agent, valuer and surveyor (Gloucestershire 1870 Post Office Directory).

James' mother, Frances Eliza ('Fanny') Lyndon was born in Dublin, Ireland in 1800, making her a little older than her husband Edmund. Her parents were George, a barrister (who died some years prior to Fanny's wedding) and Matilda Lyndon.

James' father, Edmund Fowle Wood, was born in Sandwich, Kent in 1808, the eighth son of timber merchant James Wood, and his wife Susanna. As a young man Edmund worked for the East India Company. At the time of Wood’s baptism in 1844 Edmund is described as a gentleman settler in New South Wales. Family records indicate that he ran a dairy farm. After some five years in the colony the family returned to the UK. They lived for a short time in Llansamlet, Ystradgynlais, Glamorgan, with Edmund then working as a railway contractor. Ultimately, however, the family settled in Elm Villa, Tutshill. Railway records show that Edmund continued to be employed in the Chepstow Estate Office of the Great Western Railway company until 1877 (UK Railway Employment Records, 1833-1856). He additionally acted as a land agent, valuer and surveyor (Gloucestershire 1870 Post Office Directory).

James' mother, Frances Eliza ('Fanny') Lyndon was born in Dublin, Ireland in 1800, making her a little older than her husband Edmund. Her parents were George, a barrister (who died some years prior to Fanny's wedding) and Matilda Lyndon.

EDUCATION

James was privately educated, before entering Emmanuel College, Cambridge, initially as a ‘pensioner’ (a self-funding student) in around 1862. James was successful at university, which he attended in total for around 7 years. He attained an early minor scholarship (to the value of £30) in April 1862 (Cambridge Chronicle and Journal, 26th April 1862, p4). He was granted a B.A. in 1866, this being followed by an M.A. in 1869. In 1867 he was elected as a Foundation Fellow of the college, having achieved high ranks in examinations in both classics and law (Cambridge Chronicle and Journal, 15th June 1867, p4 -5). In 1869 he was awarded the Chancellor’s Medal for Legal Studies (Cambridge Independent Press, 29th Feb 1868, p5) and also gained the Whewell scholarship in International Law. He was subsequently called to the Bar in November 1869 (Lincoln’s Inn). By the early 1870s he was acting as examiner for students of law at the University. Amongst his extracurricular activities whilst at University, rowing featured prominently. He became President of the Emmanuel College Rowing Club, and in 1867 he competed in a single’s rowing event, losing in the final heat to W.C. Crofts, of Bedford College. He lost by ‘less than half a boat’s length’ (Cambridge Chronicle and Journal, 24th August 1867, p6). In the Following year, James was no. 3 oar in the Cambridge Team, in the annual ‘blues’ Boat Race against Oxford. This was the first year in which a non-British man rowed for Cambridge, this being the cox, T.D. Warner (Trinity) of Australia. Oxford won the race by 6 lengths.

Even after leaving university James maintained an interest in rowing. In 1871 he was one of two umpires / starters in charge of the Bedford Amateur Regatta (Bedfordshire Mercury, 8th July 1871, p5). When the Master of the college, Rev. George Archdall-Gratwicke, Master for in excess of 36 years, passed away in 1871, the newspaper report of his funeral shows James G. Wood as one of the pall bearers. Rev. Edmund G. Wood, James’s older brother, was also listed amongst the mourners (Cambridge Independent Press, 23rd Sep 1871, p5).

Even after leaving university James maintained an interest in rowing. In 1871 he was one of two umpires / starters in charge of the Bedford Amateur Regatta (Bedfordshire Mercury, 8th July 1871, p5). When the Master of the college, Rev. George Archdall-Gratwicke, Master for in excess of 36 years, passed away in 1871, the newspaper report of his funeral shows James G. Wood as one of the pall bearers. Rev. Edmund G. Wood, James’s older brother, was also listed amongst the mourners (Cambridge Independent Press, 23rd Sep 1871, p5).

marriage & family

|

James married Marian Cordelia Watkins, who was raised in Chepstow, just across the river from the Wood family home in Tutshill. Marian was the youngest of three daughters born to Chepstow surgeon George Watkins and his wife Grace Emily Georgiana. Grace, who died only a year after Marian’s birth, was herself a daughter of Nathaniel Wells - owner of Piercefield House and Park, Chepstow. Marian, her father and sisters family lived in Gwy House – the site of the present day Chepstow Museum.

The marriage took place in St. Mary’s Church, Chepstow on May 13th 1873. James was by then working in London as a barrister, with an address in Kensington Park. The service was conducted, with the required consents, by his brother Rev. Edmund Wood. Several members of Marian’s maternal Wells family were in attendance, including her step grandmother, Mrs Nathaniel Wells. A local newspaper report of the wedding describes the streets of the town as having been decorated, with flowers being strewn in the bride’s path. The young couple departed to honeymoon in Derbyshire and then on the Continent (South Wales Daily News, 15th May 1873, p3). |

Nathaniel Wells 1779-1853 He was the son of a plantation owner and a house slave named Juggy. Born on St Kitts, Nathaniel was baptised and declared free in 1783, when he was 4 years old. While his father, William Wells, did marry, he had no legitimate surviving male heirs. Of his several known children born to slaves, Nathaniel was made his legal heir, being sent to school in Britain. Although some members of his father’s family contested his right to inherit, Nathaniel became a wealthy man after his father’s death, inheriting both his wealth and his plantations. At a time when people of mixed race were not commonplace within the U.K., Nathaniel became an established part of the British establishment. He married twice, having 20 children who survived to adulthood. Nathaniel moved in 1802 to the Piercefield Estate near Chepstow with his family. Nathaniel had a number of significant roles within his community, including being a Justice of the Peace, a Sheriff of Monmouthshire, and Deputy Lieutenant of the county. |

James and Marian had four children, though the first born child, Magdelen and a further daughter, Agnes, sadly did not survive infancy. Both are buried in London, where the family settled. George Llewellyn, born in July 1876, died in October 1924 in British Columbia (in a motoring accident). Lesley Wood, great granddaughter of James, has kindly provided the following information about Llewellyn (as George preferred to be known): 'After leaving Cambridge without a degree, he was sent to Ceylon to work on a tea plantation (but instead) settled to work at a Catholic Boys’ school in Colombo (where) he studied to convert to Catholicism’. Llewellyn married Mary Louise Plâté in Colombo. On return to Britain the couple lived for a short time in North Wales, before moving to and settling on Thetis Island, British Colombia, Canada. They went on to have 9 children, of whom 7 survived to adulthood. Family reports indicate that James and Llewellyn had something of a strained relationship, partly due to Llewellyn’s decision to convert to Roman Catholicism. Perhaps due to this and the distance between Canada and London, the two families did not ever meet after Llewellyn emigrated. However, one of Llewellyn’s sons has shared with Lesley Wood the information that, ‘Below the tree on Christmas morning, we’d find boxes of presents sent from London...money was tight and the Christmas largesse was greatly appreciated!' Their second child to survive into adulthood was daughter Grace Editha born in March 1881, who passed away, unmarried in December 1933.

In later life the Wood family moved to 115 Sutherland Avenue, Maida Vale. Family records show that James, a well off and successful barrister, bought a number of properties, many of them near to his brother’s church in Cambridge, which he rented out. When he died he was a wealthy man, his will showing an overall estate of just over £75.000 (National Probate Calendar, Index of Wills, Ancestry.co.uk).

In later life the Wood family moved to 115 Sutherland Avenue, Maida Vale. Family records show that James, a well off and successful barrister, bought a number of properties, many of them near to his brother’s church in Cambridge, which he rented out. When he died he was a wealthy man, his will showing an overall estate of just over £75.000 (National Probate Calendar, Index of Wills, Ancestry.co.uk).

career

James became a lawyer at 7 New Square, Lincoln’s Inn, London. He had links with a company called Hardy and Page, who were frequently commissioned to report on and prepare transcripts and translations of records held at the Public Record Office (now the National Archives). This remit coincided very closely with James' own particular interest in antiquarian pursuits, with the research methods he would have employed for his legal work transferring readily to that required for many of his own published works. A former colleague wrote the following about James' professional life in an obituary, published in The Times on Jan 14th 1928:

“He took a first class in the Classic Tripos of 1866, rowed in the Cambridge Boat of 1868 and was an enthusiastic oarsman. Although he never took ‘silk’ he was a very eminent and learned Chancery counsel, especially with regard to mines and minerals. Probably he would have been elected a Bencher of Lincoln’s Inn earlier but for his modest and retiring disposition. He will be much missed ...he has been a familiar figure for some 60 years"

“He took a first class in the Classic Tripos of 1866, rowed in the Cambridge Boat of 1868 and was an enthusiastic oarsman. Although he never took ‘silk’ he was a very eminent and learned Chancery counsel, especially with regard to mines and minerals. Probably he would have been elected a Bencher of Lincoln’s Inn earlier but for his modest and retiring disposition. He will be much missed ...he has been a familiar figure for some 60 years"

AUTHOR

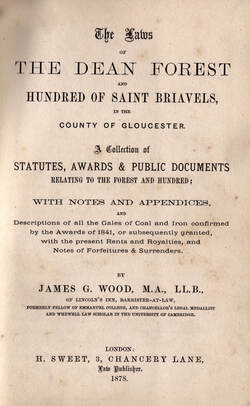

Once an established barrister James also began to further develop his other interests, which included studying and writing about a range of pursuits , especially those with antiquarian or meteorological foci. He wrote extensively about the area in which he was raised (Tutshill and Chepstow), and to which he returned as a visitor throughout his adult life, utilising source material, often with a legal slant, to inform and guide his work. Of all his published work it is one that has had the longest lasting impact, informing his readership of the laws and statutes that have contributed to the emergence of the Forest of Dean as it was (and continues in many respects to be) until the present day.

The Laws of the Dean Forest and Hundred of St Briavels, in the County of Gloucestershire (1878).

In this single volume of over 400 pages Wood brought together the key aspects of all official ‘Statutes, Awards and Public Documents’ from 1688 to 1871, having relevance to the Forest. To this source material is added notes and footnotes by the author, some to clarify and others to explain the impact of the various points of law contained in the source materials. The Laws and other information would, the author hoped, amongst other things:

The Laws of the Dean Forest and Hundred of St Briavels, in the County of Gloucestershire (1878).

In this single volume of over 400 pages Wood brought together the key aspects of all official ‘Statutes, Awards and Public Documents’ from 1688 to 1871, having relevance to the Forest. To this source material is added notes and footnotes by the author, some to clarify and others to explain the impact of the various points of law contained in the source materials. The Laws and other information would, the author hoped, amongst other things:

Furnish not only members of the legal profession, but mine owners and others interested in the district, with an accurate work of reference upon the existing mines of the Hundred, and the special laws and regulations affecting them.

A brief outline of the overall history of the Forest is included in the book’s introduction, though the author refers readers in search of an historical or descriptive account to the earlier book written by the Rev H.G. Nicholls (1858).

The book provides a plethora of fascinating information on a range of topics, and includes details of all coal mines, iron mines and quarries extant in 1831, and also cites others granted in the interim period, prior to the publication of the book. There is discussion regarding laws around the right to common sheep in the Forest, mention of the deforestation during the time of Sir John Wintour and much more, which makes it a fascinating if highly detailed volume to any with an interest in the back story to many of the current rights and privileges Foresters still fight to maintain in the present day.

Such a book required a skilled mind, aware of the law and able to interpret the intent of the sometimes complex legal terminology and phrasing used, especially in material from earlier times. James' legal knowledge, coupled with his keen interest in the locality, would have been of fundamental importance in the composition of this book, and made him uniquely placed to bring it to publication. Some 70 years after its publication a supplement ‘Laws of the Forest’ was written by Cyril Hart. This book provided information about new and revised laws and statutes that had come into effect over the intervening period, and was published with the consent of James' descendants in Canada. A limited edition reprint of Wood’s book was published in 2000, with a forward penned by Cyril Hart.

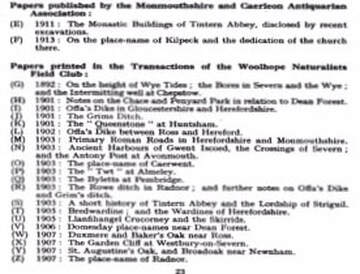

James wrote several other books and a number of papers, some related to the locality and others reflecting his broader interests, such as meteorology. He was also a frequent letter writer to newspapers on subjects reflecting his many interests. In June 1885, just after the incident which saw the Buckstone at Staunton tumbled from its balance point, James wrote a letter to the London Evening Standard (London Evening Standard, 13th June 1885, p2). He corrects any perception possibly engendered in readers that with its loss, any reason for visiting the area has also gone. He describes the views still offered from the original location of the stone, across to the Malvern Hills and into Wales. His respect for the Dean is clearly in evidence. As his great granddaughter Lesley Wood notes, despite living in London for much of his adult life, James was, and remained, active in the Monmouthshire and Caerleon Antiquarian Association in which he served as secretary. His father-in-law George Watkins was also a member of this Society. Further afield, he was also a Fellow of the Geological Society and of the Royal Meteorological Society.

An interest in the climate and related issues led to James being very interested in topics such as the tidal reach of the Wye at Chepstow – about which he kept records for a number of years.

The book provides a plethora of fascinating information on a range of topics, and includes details of all coal mines, iron mines and quarries extant in 1831, and also cites others granted in the interim period, prior to the publication of the book. There is discussion regarding laws around the right to common sheep in the Forest, mention of the deforestation during the time of Sir John Wintour and much more, which makes it a fascinating if highly detailed volume to any with an interest in the back story to many of the current rights and privileges Foresters still fight to maintain in the present day.

Such a book required a skilled mind, aware of the law and able to interpret the intent of the sometimes complex legal terminology and phrasing used, especially in material from earlier times. James' legal knowledge, coupled with his keen interest in the locality, would have been of fundamental importance in the composition of this book, and made him uniquely placed to bring it to publication. Some 70 years after its publication a supplement ‘Laws of the Forest’ was written by Cyril Hart. This book provided information about new and revised laws and statutes that had come into effect over the intervening period, and was published with the consent of James' descendants in Canada. A limited edition reprint of Wood’s book was published in 2000, with a forward penned by Cyril Hart.

James wrote several other books and a number of papers, some related to the locality and others reflecting his broader interests, such as meteorology. He was also a frequent letter writer to newspapers on subjects reflecting his many interests. In June 1885, just after the incident which saw the Buckstone at Staunton tumbled from its balance point, James wrote a letter to the London Evening Standard (London Evening Standard, 13th June 1885, p2). He corrects any perception possibly engendered in readers that with its loss, any reason for visiting the area has also gone. He describes the views still offered from the original location of the stone, across to the Malvern Hills and into Wales. His respect for the Dean is clearly in evidence. As his great granddaughter Lesley Wood notes, despite living in London for much of his adult life, James was, and remained, active in the Monmouthshire and Caerleon Antiquarian Association in which he served as secretary. His father-in-law George Watkins was also a member of this Society. Further afield, he was also a Fellow of the Geological Society and of the Royal Meteorological Society.

An interest in the climate and related issues led to James being very interested in topics such as the tidal reach of the Wye at Chepstow – about which he kept records for a number of years.

|

In 1892 James exchanged letters, published in the London Evening Standard, with a resident of Chepstow, F. H. Worsley-Benison. There was in particular much discussion regarding a ‘tidal wave’ which occurred on Oct 17th 1883 (London Evening Standard, 15th Oct 1892, p6). The outcome of the letter exchange is that Worsley-Benison wrote a letter of apology to the paper, stating that an ‘unaccountable error’ had occurred in the taking of the measurement on which he had relied. The 1883 tide had been abnormally high, reaching a height of some 22 inches above the usual Spring tide limit.

|

In a further letter to the London Evening Standard in 1887, Wood once more demonstrates his interest in and knowledge of meteorology, this time writing about the likelihood of frosts in the month of October. He speaks of owning a ‘Casella instrument’, and challenges usage of the inaccurate / incorrect phrase ‘degrees of frost’ – a phrase which he describes as ‘absurdly incorrect’ (London Evening Standard, 17th Oct 1887, p3).

Again away from those of his written works with a ‘local’ focus, Wood clearly was adept at languages, this enabling him to translate the works of Greek philosopher Theophrastus, on winds and weather. The costs of publication were defrayed by his long term friend, meteorologist G. J. Symons, who also served as the book’s editor. Despite its title and the obscure source material, and in common with books such as ‘Laws’, the book was intended not for scholars ‘but for the general public and especially for that section of it interested in meteorology’ (Teignmouth Post and Gazette, 29th Nov 1895, p2)

Again away from those of his written works with a ‘local’ focus, Wood clearly was adept at languages, this enabling him to translate the works of Greek philosopher Theophrastus, on winds and weather. The costs of publication were defrayed by his long term friend, meteorologist G. J. Symons, who also served as the book’s editor. Despite its title and the obscure source material, and in common with books such as ‘Laws’, the book was intended not for scholars ‘but for the general public and especially for that section of it interested in meteorology’ (Teignmouth Post and Gazette, 29th Nov 1895, p2)

BOOKS & PAPERS

The Laws of the Dean Forest and Hundred of St Briavels, in the County of Gloucestershire. H Sweet, Chancery Lane, London (1878)

A limited edition reprint, with forward by Cyril Hart, was published by Ross Old Books [Cinderford] and Past and Present Books [Coleford] in 2000

Theophrastus on Winds and Weather Signs. E. Stanford, London (1894)

The Lordship, Castle and Town of Chepstow, otherwise Striguil. Mullock and Sons, Newport (1901)

Points of Interest on the route by the railway from Grange Court Junction to Chepstow, thence by main road to Caerwent (After 1901)

William Herbert, Earl of Pembroke: A Sequel to the Battle of Danesmoor, The Antiquary, London, Vol3, Iss. 1 pp8-11 (1907)

Tintern Abbey, Archaeologia Cambrensis, Vol. 9, pp. 49-64 (1909)

The Manor and Mansion of Moyne’s Court. Mullock and Sons, Newport 1910

The Island Chapel of St. Twrog in the Severn, and the Manors of Tintern Parva and Trellech. Mullock and Sons, Newport (1920)

A limited edition reprint, with forward by Cyril Hart, was published by Ross Old Books [Cinderford] and Past and Present Books [Coleford] in 2000

Theophrastus on Winds and Weather Signs. E. Stanford, London (1894)

The Lordship, Castle and Town of Chepstow, otherwise Striguil. Mullock and Sons, Newport (1901)

Points of Interest on the route by the railway from Grange Court Junction to Chepstow, thence by main road to Caerwent (After 1901)

William Herbert, Earl of Pembroke: A Sequel to the Battle of Danesmoor, The Antiquary, London, Vol3, Iss. 1 pp8-11 (1907)

Tintern Abbey, Archaeologia Cambrensis, Vol. 9, pp. 49-64 (1909)

The Manor and Mansion of Moyne’s Court. Mullock and Sons, Newport 1910

The Island Chapel of St. Twrog in the Severn, and the Manors of Tintern Parva and Trellech. Mullock and Sons, Newport (1920)

James; great granddaughter, Lesley Wood writes the following in her unpublished history of the family:

‘JG is remembered – at least in his beloved Wye Valley – for his antiquarian studies, rather than his legal abilities. This is probably exactly the way he would wish to be remembered. A painstaking and exacting researcher, JG never contented himself with building on the work of other historians if he could go back and review the original source documents for himself’.

Lesley adds the following extract in his own words, from the preface of his book entitled ‘The Island Chapel of St. Twrog in Severn and the Manors of Tintern, Parva and Trellech’

‘JG is remembered – at least in his beloved Wye Valley – for his antiquarian studies, rather than his legal abilities. This is probably exactly the way he would wish to be remembered. A painstaking and exacting researcher, JG never contented himself with building on the work of other historians if he could go back and review the original source documents for himself’.

Lesley adds the following extract in his own words, from the preface of his book entitled ‘The Island Chapel of St. Twrog in Severn and the Manors of Tintern, Parva and Trellech’

…[these] works [are] produced…solely from a close affection for a country intimately known to me over a very long number of years, and a desire that accurate knowledge, as far as I could impart it, should take the place of insufficient, and to a large extent inaccurate information which for a long time had obscured…its history.

the society for maintenance of the faith

James' brother, Edmund, also attended Emmanuel College, Cambridge and on completion of his degree he entered the ministry, becoming curate at St Clements Church, Cambridge in 1865. The Vicar at the time was Rev. Arthur Ward, whom Edmund succeeded on his death in 1895. Edmund was a staunch Anglo-Catholic and with James was a founding member of the Society for Maintenance of the Faith, a body set up in 1873 to ‘promote and maintain Catholic teaching and practice by all means morally and canonically lawful’. He remained closely involved in the Movement, serving as Master for several terms. The Society was dedicated to upholding Catholic (not Roman Catholic) teaching and practice within the Church of England, principally through acquiring patronage of certain livings (through gift or bequest) that could then be awarded to priests holding Anglo-Catholic ideals (The Society’s History at smftrust.org.uk). In November 1894 Edmund was reported in a number of newspapers due to his involvement in a Holy Eucharist service at St Clements Church, Norwich, in which he ‘enunciated the dogma that souls in purgatory may be relieved of a portion of their suffering, and their movement towards Paradise expedited, through the prayers of the faithful here on earth’ (Reynold’s Newspaper, 18th Nov 1894, p5). The newspaper report concludes that this was the first time a Holy Eucharist (on behalf of the departed) had ever been offered at Norwich in ‘a church of the establishment’ (C of E). Edmund wrote a number of books with theological themes, and he was made an honorary canon of Ely Cathedral in 1911, for his work. Family records suggest he may also have assisted James by carrying out background research on his behalf at the University library in Cambridge. Edmund remained at St Clements Church for much of his long life and is buried in the churchyard there, through special dispensation, as it had closed to new burials by the time of his death. He died in December 1932, after a decline in health which left him unable fully to manage his own affairs. Family records indicate that he was helped in financial matters by his niece (James’ daughter Grace Edith) in these latter years. Edmund and James remained extremely close throughout their lives. A quote by Edmund, at the time of James' death, later appeared in an ‘In Memoriam’ published after Edmund’s own death. This quote, kindly provided by Lesley Wood, reads ‘There never were two brothers devoted to each other as we were’ (Church Times, Dec 22, 1932).

death

James died in January 1928, his wife Marian surviving him by only a year. Both are buried, with their daughter Grace, in Paddington Cemetery, London. Sadly the original gravestone marking the burial place of JGW and his wife was destroyed or removed during World War 2. A replacement stone was placed in the original location by family in 2008.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Our special thanks go to Lesley Wood, great granddaughter of James G. Wood, who has kindly shared with us material from her unpublished biographical research into her family history. In her contact with Reading the Forest Lesley notes:

“I grew up only knowing that my great grandfather was named James (like my Dad), had been a lawyer and 'written a book.' When I got interested in family history, one of my sisters one day handed me what she said was 'great grandfather's book!' It was a thin little book and my first reaction was 'great grandfather wasn't named Cyril Hart!' But, happily, Cyril's book did contain a photo of James George Wood, and also a wonderful footnote that gave the names of his father, brother, wife and father in law. This finally gave me some info from which I could start researching. (I was also delighted to make contact with Cyril before his death.)”

Our special thanks go to Lesley Wood, great granddaughter of James G. Wood, who has kindly shared with us material from her unpublished biographical research into her family history. In her contact with Reading the Forest Lesley notes:

“I grew up only knowing that my great grandfather was named James (like my Dad), had been a lawyer and 'written a book.' When I got interested in family history, one of my sisters one day handed me what she said was 'great grandfather's book!' It was a thin little book and my first reaction was 'great grandfather wasn't named Cyril Hart!' But, happily, Cyril's book did contain a photo of James George Wood, and also a wonderful footnote that gave the names of his father, brother, wife and father in law. This finally gave me some info from which I could start researching. (I was also delighted to make contact with Cyril before his death.)”

Thanks to volunteer Caroline Prosser-Lodge for the research and writing of this page.